An Academic Look At The Systemic Oppression of Asexuality

The Statistics Behind Asexual Discrimination

Little is known about asexuality, and even less is known about the discrimination that asexuals face. Few studies have been conducted evaluating the effect of compulsory sexuality, and those that have been done are qualitative rather than quantitative. According to a submission to the Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, the study of asexuality is “thirty years behind other sexual minorities”. This paper is not meant to be a complete guide to compulsory sexuality, but rather the tip of the iceberg and the beginning of the field of Asexual Studies.All sources will be uploaded under the Works Cited page.

Contact @asexualresearch on Twitter or [email protected] for articles that should be added, questions, or concerns!

What is Systemic Oppression?

Understanding The Framework Of Oppression

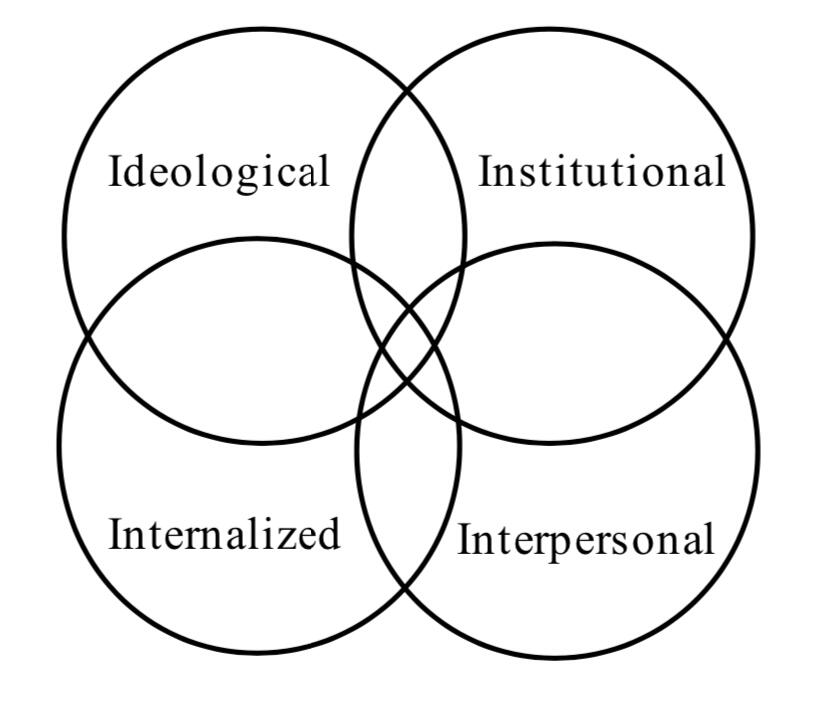

A common misconception is that institutional oppression (which is also sometimes called systemic oppression) is merely laws against a certain group of people. In reality it is often much more complex than that; institutional oppression takes form in various systems within society. This could be the legal system, the medical system, the educational system, and more. In order to understand the framework of oppression, many activists use “The Four I’s Of Oppression” by The Chinook Fund. The definition given of institutional oppression is “the idea that one group is better than another group and has the right to control the other gets embedded in the institutions of the society--the laws, the legal system and police practice, the education system and schools, hiring policies, public policies, housing development, media images, political power, etc”. The full document is attached below.Contact @asexualresearch on Twitter or [email protected] for articles that should be added, questions, or concerns!

THE FOUR "I's" OF OPPRESSIONIdeological Oppression

First, any oppressive system has at its core the idea that one group is somehow better than another, and in some measure has the right to control the other group. This idea gets elaborated in many ways-- more intelligent, harder working, stronger, more capable, more noble, more deserving, more advanced, chosen, normal, superior, and so on. The dominant group holds this idea about itself. And, of course, the opposite qualities are attributed to the other group--stupid, lazy, weak, incompetent, worthless, less deserving, backward, abnormal, inferior, and so on.Institutional Oppression

The idea that one group is better than another group and has the right to control the other gets embedded in the institutions of the society--the laws, the legal system and police practice, the education system and schools, hiring policies, public policies, housing development, media images, political power, etc. When a woman makes two thirds of what a man makes in the same job, it is institutionalized sexism. When one out of every four African-American young men is currently in jail, on parole, or on probation, it is institutionalized racism. When psychiatric institutions and associations “diagnose” transgender people as having a mental disorder, it is institutionalized gender oppression and transphobia. Institutional oppression does not have to be intentional. For example, if a policy unintentionally reinforces and creates new inequalities between privileged and non-privileged groups, it is considered institutional oppression.Interpersonal Oppression

The idea that one group is better than another and has the right to control the other, which gets structured into institutions, gives permission and reinforcement for individual members of the dominant group to personally disrespect or mistreat individuals in the oppressed group. Interpersonal racism is what white people do to people of color up close--the racist jokes, the stereotypes, the beatings and harassment, the threats, etc. Similarly, interpersonal sexism is what men do to women-- the sexual abuse and harassment, the violence directed at women, the belittling or ignoring of women's thinking, the sexist jokes, etc.

Most people in the dominant group are not consciously oppressive. They have internalized the negative messages about other groups, and consider their attitudes towards the other group quite normal.

No "reverse racism". These kinds of oppressive attitudes and behaviors are backed up by the institutional arrangements. This helps to clarify the confusion around what some claim to be "reverse racism". People of color can have prejudices against and anger towards white people, or individual white people. They can act out those feelings in destructive and hurtful ways towards whites. But in almost every case, this acting out will be severely punished. The force of the police and the courts, or at least a gang of whites getting even, will come crashing down on those people of color. The individual prejudice of black people, for example, is not backed up by the legal system and prevailing white institutions. The oppressed group, therefore, does not have the power to enforce its prejudices, unlike the dominant group.

For example, the racist beating of Rodney King was carried out by the institutional force of the police, and upheld by the court system. This would not have happened if King had been white and the officers black.

A simple definition of racism, as a system, is: RACISM = PREJUDICE + POWER.

Therefore, with this definition of the systemic nature of racism, people of color cannot be racist. The same formula holds true for all forms of oppression. The dominant group has its mistreatment of the target group embedded in and backed up by society's institutions and other forms of power.Internalized Oppression

The fourth way oppression works is within the groups of people who suffer the most from the mistreatment. Oppressed people internalize the ideology of inferiority, they see it reflected in the institutions, they experience disrespect interpersonally from members of the dominant group, and they eventually come to internalize the negative messages about themselves. If we have been told we are stupid, worthless, abnormal, and have been treated as if we were all our lives, then it is not surprising that we would come to believe it. This makes us feel bad.

Oppression always begins from outside the oppressed group, but by the time it gets internalized, the external oppression need hardly be felt for the damage to be done. If people from the oppressed group feel bad about themselves, and because of the nature of the system, do not have the power to direct those feelings back toward the dominant group without receiving more blows, then there are only two places to dump those feelings--on oneself and on the people in the same group. Thus, people in any target group have to struggle hard to keep from feeling heavy feelings of powerlessness or despair. They often tend to put themselves and others down, in ways that mirror the oppressive messages they have gotten all their lives. Acting out internalized oppression runs the gamut from passive powerlessness to violent aggression. It is important to understand that some of the internalized patterns of behavior originally developed to keep people alive--they had real survival value.

On the way to eliminating institutional oppression, each oppressed group has to undo the internalized beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that stem from the oppression so that it can build unity among people in its group, support its leaders, feel proud of its history, contributions, and potential, develop the strength to challenge patterns that hold the group back, and organize itself into an effective force for social change.Internalized Privilege

Likewise, people who benefit the most from these systems internalize privilege. Privileged people involuntarily accept stereotypes and false assumptions about oppressed groups made by dominant culture. Internalized privilege includes acceptance of a belief in the inherent inferiority of the oppressed group as well as the inherent superiority or normalcy of one’s own privileged group. Internalized privilege creates an unearned sense of entitlement in members of the privileged group, and can be expressed as a denial of the existence of oppression and as paternalism.It should be clear that none of these four aspects of oppression can exist separately. As the diagram [above] suggests, each is completely mixed up with the others. It is crucial at see any oppression as a system. It should also be clear that trying to challenge oppression in any of the four aspects will affect the other three.”

What Is Compulsory Sexuality?

The Systemic Privileging of Allosexuality

Compulsory sexuality (also call amanormativity or sexusociety) is "the assumption that all people are sexual and to describe the social norms and practices that both marginalize various forms of nonsexuality and compel people to experience themselves as desiring subjects, take up sexual identities, and engage in sexual activity" (Gupta). Several scholars have begun to take an in-depth look into this field of study.All sources will be uploaded under the Works Cited page.Contact @asexualresearch on Twitter or [email protected] for articles that should be added, questions, or concerns!

Exploring the Experiences of Heterosexual and Asexual Transgender People (The University of Tampa And Vanderbilt University)

“Asexual organizing also presents a challenge to asexual discrimination. Researchers across fields have provided evidence for “asexphobia” or “anti- asexual bias/prejudice” such that asexuals are understood as “deficient,” “less human, and disliked.”28 Asexphobia exists at the level of attitudes that have negative effects on asexual people such as when they are interrogated and asked intrusive questions about their bodies and sexual lives, or when they are presented with “denial narratives” to undermine the validity of their asexual- ity.29 In figure 0.2, from the zine Taking the Cake, Maisha indicates the many ways in which asexuality can be undermined. For example, people might sug- gest that an ace person is repressed, closeted, incapable of obtaining sex from others, or in an immature phase. These dismissive comments are informed by ableist ideas, such as that disability prevents the capacity for sex and that ability rests on an enjoyment of and desire for sex as well as by compulsory sexuality, which suggests that sex is necessary, liberatory, and integral to hap- piness and well-being. Discrimination can also take on the form of social and sexual exclusion, including in queer contexts: through “conversion” practices in medical and clinical environments to encourage asexuals to have sex, with unwanted and coerced sex in partner contexts, through the misdiagnosis of sexual desire disorders in people who are asexual, and with invisibility, toxic attention, or the fetishization of asexual identity.31 Recognizing discrimina- tion is important because it refuses to see individual acts against asexuals as incidental, providing a systemic view on patterns of “dislike” against asexuals.“

Crisis and safety: The asexual in sexusociety (American Psychological Association)

"The ‘sexual world’ is for asexuals very much akin to what patriarchy is for feminists

and heteronormativity for LGBTQ populations, in the sense that it constitutes the

oppressive force against which some sort of organizing and rebellion must take 4

place.To be quite a bit more specific, what are sexusociety’s favoured repetitions? Despite the diversity of feminist articulations on this topic (in other words the topic of what patriarchy ‘wants’ us to do), most feminists would likely give a similar answer: coital sex, sex with a purpose (be it reproduction or male orgasm), heterosexual and heteronormative sex, sex within marriage or coupledom, the importance of two, and a sexuality that amounts to little more than the sum of these. Gayle Rubin deems this a ‘hierarchical system of sexual value’, outlining textually and pictorially which acts are privileged and which collectively feared and despised (2006 [1984]: 529). Most relevant for this discussion of asexuality, however, is the favoured repetition of sex, understood mostly in a coital and heteronormative sense, and the compulsion to repeat sexually, as opposed to say intellectually (though I am not saying that the two do not overlap and interlace).These snippets of our cultural necessity to have sex, most prefer- ably heterosexually and coitally, are relevant to this discussion of asexuality because it is against such normative scripts of sexual repetition that pathologies of non-sex are constructed.In a certain sense, the absence of sexual ‘urges’ becomes more problematic

than an overabundance of them, as is strangely crystallized by a triad of sexologists in 1998 who ‘plead for the introduction of a category on excessive (or hyperactive) sexual desire’, whereas the addition of new and varied sexual lack pathologies does not need to be pleaded for (Vroege et al., 2001: 239). And as Gavey suggests, the problem may not lie in disordered women, so much as in a lack of interest in the sex that is being repeated as ‘normal’, ‘the kind of sex on offer’ (2005: 112). Leonore Tiefer reminds us that we should be wary of regarding the DSM as a neutral source indexing reality, but remember instead that it is itself a cultural production invested in a gendered and heterosexist system (1995: 97–102).This impetus to pathologize those who are not sexual enough, or who do not repeat sexuality faithfully to ‘the norm’, is indicative of which repetitions are favoured by sexusociety. But it also, and more relevantly, embodies sexusociety’s interest in maintaining a society that repeats along sexual lines.David Jay is subsequently coerced to reveal details of his asexuality, he is positioned as an object of sexual lack and is altogether bewildering for the hosts (Jay, 2007b). He must disclose details of his non-sexual past (‘do you masturbate?’) so that the hosts and the audience may assess to what extent his ‘non’-sexuality is ‘true’ (and of course, faithful repetition is impossible and any detail from the past may be fished out as counterevidence to his claims).It also demonstrates sexusociety’s employ- ment of the confession as a means to correct incorrect repetition. So while David Jay confesses absence, the hosts strive to reconfigure absence into a sexual presence that resembles the ideal, in this case, the sexual ideal. Improper sexual repetitions (or in the case of asexuality, the paucity of sexual repetitions) are remedied with the guidance of other sexual subjects who are more faithful to the norms of sexual acting (presumably the hosts of The View). The confession is thus one of those very special moments within sexusociety when wrongs may be righted, when faulty repetitions may be discouraged or made to appear fraudulent, and when difference or absence may be permutated into a correct presence. Sex, and now also its absence, ‘has to be put into words’ (Foucault, 1990 [1978]: 32).Asexuality would do well to recognize that there is no vacation away from sexusocial discourse; even the micro safe space of the asexual body is in fact embedded within sexusociety. "

Lessons from bisexual erasure for asexual erasure (University of Amsterdam)

"Bisexual erasure is undoubtedly powerful; however, certain points made within this essay could lead one to conclude that asexual erasure must be even more oppressive. Asexuality does not stop at changing the rules of the game of sexuality as bisexuality does, but broadly refuses to even play the game. It is not that sex is undermined because the asexual is simply sex blind (a blindness which, incidentally, is greater than that sex blindness found in bisexuals); rather, sex is undermined since the private erotic realm that produces and sustains it does not exist for the asexual. And it is not so much monogamy that is threatened by asexuality (though the sexual dynamics within it are), but instead intimate relationships in general – a threat presented most acutely by the aromantic asexual. Such is the more important destabilising power of asexuality for the norms allosexuality would have preserved, and consequently greater is the erasure asexuality ought to receive."

Asexual (GLOBAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANSGENDER, AND QUEER HISTORY)

“Asexual organizing also presents a challenge to asexual discrimination. Researchers across fields have provided evidence for “asexphobia” or “anti- asexual bias/prejudice” such that asexuals are understood as “deficient,” “less human, and disliked.”28 Asexphobia exists at the level of attitudes that have negative effects on asexual people such as when they are interrogated and asked intrusive questions about their bodies and sexual lives, or when they are presented with “denial narratives” to undermine the validity of their asexual- ity.29 In figure 0.2, from the zine Taking the Cake, Maisha indicates the many ways in which asexuality can be undermined. For example, people might sug- gest that an ace person is repressed, closeted, incapable of obtaining sex from others, or in an immature phase. These dismissive comments are informed by ableist ideas, such as that disability prevents the capacity for sex and that ability rests on an enjoyment of and desire for sex as well as by compulsory sexuality, which suggests that sex is necessary, liberatory, and integral to hap- piness and well-being. Discrimination can also take on the form of social and sexual exclusion, including in queer contexts: through “conversion” practices in medical and clinical environments to encourage asexuals to have sex, with unwanted and coerced sex in partner contexts, through the misdiagnosis of sexual desire disorders in people who are asexual, and with invisibility, toxic attention, or the fetishization of asexual identity.31 Recognizing discrimina- tion is important because it refuses to see individual acts against asexuals as incidental, providing a systemic view on patterns of “dislike” against asexuals.“

Asexual Erotics

"Researchers across fields have provided evidence for “asexphobia” (Kim 2014) or “anti-asexual bias/prejudice” such that asexuals are understood as “deficient,” “less human, and disliked” (MacInnis and Hodson 2012, 740). Asexphobia exists at the level of attitudes that have negative effects on asexual people when they are interrogated and asked intrusive questions about their bodies and sexual lives, or when they are presented with “denial narratives” to undermine the validity of their asexuality (MacNeela and Murphy 2015). Discrimination can also take the form of social and sexual exclusion, including in queer contexts; through “conver- sion” practices in medical and clinical environments to encourage asexuals to have sex; with unwanted and coerced sex in partner contexts; through the misdiagnosis of sexual desire disorders in people who are asexual; and with invisibility and toxic attention or the fetishization of asexual identity (Ginoza et al. 2014; Przybylo 2014; Chasin 2015; Cerankowski 2014). Recognizing discrimi- nation is important because it refuses to see individual acts against asexuals as incidental, providing a systemic view on patterns of “dislike” against asexuals.Third, queer and feminist research definitions of asexuality also place asexuality in direct dialogue with larger power structures and patterns of injustice. Devel- oping the important term compulsory sexuality by drawing on the work of the legal scholar Elizabeth F. Emens (2014), Kristina Gupta (2015) elaborates on the ways in which compulsory sexuality is a system that encourages some people to have sex, even while banning marginalized groups from sexual expression through the process of “desexualization.” “Sexusociety,” or a society organized around sex (Przybylo 2011), partakes in desexualization, as Kim’s work explores, to render marginalized groups such as people with disabilities, lesbians and transgender people, children and older adults, people of size, and some racialized groups as “asexual” by default—misusing the term asexuality in the process. For example, transgender people have historically needed to feign asexuality and demonstrate disgust for homosexual sex in order to have their surgeries approved and their trans identities confirmed as “valid” by medicine (Valentine 2007). More broadly, desexualization ranges from discourses around people with disabilities not being capable of sex or not being desirable to eugenics-based initiatives for managing a population through controlling reproduction via methods of coerced sterilization.

Desexualization and compulsory sexuality are also linked to hypersexualization, or the branding of some groups and most especially gay men and racialized groups as excessively sexual and lascivious and thus in need of population management. Treatment of people with AIDS in the 1980s, for example, and the pivoting of the “AIDS epidemic” as “God’s punishment for being gay” demonstrate how the deployment of hypersexualization, in combination with homophobia, can have lethal effects on marginalized groups. Ianna Hawkins Owen (2014) discusses how compulsory sexuality has uneven racial histories, such that whiteness has tended to emulate an “asexuality-as-ideal” as demonstrative of a form of innocence, moral control, and restraint, whereas black people have often been positioned as hypersexual so as to justify chattel slavery, lynching, and other instruments of racism. Hypersexualization and desexualization have thus been used historically and are in the present used as forms of social control and oppression, toward the maintenance of a white, able-bodied, hetero- patriarchal nation-state. Feminist and queer research on asexuality thus invites examinations of the intersectional histories and present-day realities of compulsory sexuality."

The Violence of Heteronormative Language Towards the Queer Community

“ Asexuality is a spectrum that is characterized by a lack of sexual attraction to other people; asexuals might still experience romantic attraction to others, or they might not, in which case they would also be aromantic. In attempting to “explain” their sexuality in ways that fit heteronormative standards, asexuals can unintentionally contribute to their own erasure.

Common ways of trying to make asexuality accessible to a heterosexual audience include saying that “asexuals are just like everyone else, but without the sex” or explaining asexuality in terms of food— for example, some people like and crave cake, while others do not. This metaphor is problematic as it implies that asexuality is only a minor aspect of one’s personality, as easily removed or overlooked as one’s food preferences. Similarly problematic are discussions of sexual attraction in society at large (particularly in the context of masculinity) that assert that attraction is a necessary part of the human experience.

These kinds of definitions put asexuals in an uncomfortable spot. Under heteronormativity, they would not be considered “normal” and might not easily fit into other heteronormative categories (for example, an asexual could be transgender and homoromantic, and thus would not easily fit into the heteronormative mold). For this reason, asexuals feel the need to liken themselves to heterosexuals and prove that they are “normal” and can fit in. The implications of such statements are that everyone else in the queer community is somehow abnormal or not like “everyone else.”

Such analogies present asexuality as a watered- down version of another sexuality—heterosexuality lite, so to speak—erasing asexual experiences. This

is a form of heteronormative language violence, as it can cause asexuals to be pushed away from the broader queer community because their deviance from the heteronormative standard may not be as immediately obvious as, for example, a homosexual transgender person’s might. In addition, as a result of the language above, “gate-keeping” within the asexual community can arise, where some are excluded because they do not seem “queer enough”—for example, a heteroromantic demisexual (a sexuality on the asexual spectrum where one can feel sexual attraction to another ONLY after a strong emotional bond has been formed) could “pass” as straight, and thus might be seen as not needing the support of the community (Asexual 1). After all, if they were “just like everyone else” then why would they need a special community for support?

Though isolated from the LGBTQIA community (a community perhaps best suited to understand the experience of living in a world that sets a certain pattern of behavior and feelings that they do not share as “normal”) asexuals will not necessarily find the support they need in the broader heteronormative context of society.

Heteronormative language is violent, as it diminishes the identity of bisexuals and asexuals while limiting their ability to find support within the communities that are best suited to their experiences. Heteronormative language also denies asexuals the ability to express their experiences without being questioned, and invalidates the asexual identity—a form of violence. Similar to the argument that bisexuals are “confused” or “halfway in the closet,” the oversimplification of the asexual identity through cute analogies implies that asexuality is a quirk or a phase, rather than a valid identity and a major part of a person’s personality. Language that trivializes asexuality limits the ability of asexuals to express themselves, their experiences and their sexuality without fear of repercussions, whether that is not being taken seriously or being treated as an outsider. It normalizes the idea that heterosexuality is “normal” and preferable to any other orientation, to the point where those who identify differently must prove how like heterosexuals they are to be afforded respect. Thus, the erasure of asexuals and bisexuals is a form of heteronormative language violence. (Asexual 1)”

A mystery wrapped in an enigma – asexuality: a virtual discussion

“My general impression from the U.S. context is that the negativity directed at asexual individuals is similar in some ways to the negativity directed at other sexual (and gender) minorities: asexual individuals, like other sexual minorities, may be perceived as mentally or physically ill, asexual individuals may feel alienated in social settings organized to facilitate heterosexual coupling, and asexual individuals may be denied legal and/or social recognition of their most important relationships. On the other hand, to a perhaps greater extent than other sexual minorities, asexual individuals are often denied ‘epistemic authority’ in regards to their own (a)sexuality. In other words, asexual individuals may be met with the reaction that they can’t really know that they are asexual – maybe they haven’t met the right person yet, maybe they are ‘late bloomers,’ maybe they are unconsciously repressing their sexual desires, maybe there is a physical cause of their asexuality that simply hasn’t been found yet.”

Towards a Historical Materialist Concept of Asexuality and Compulsory Sexuality

Theoretical Issues in the Study of Asexuality

“Simultaneously, the unquestioned presumption of the sexual norm—of sexuality as the norm—dictates that asexual people will very frequently pass as sexual people in everyday lives whether they want to or not. Asexual people therefore live an analogous biculturalism to the one Brown described of lesbians and gay men, and so incorporating the perspectives of asexual people into the domain of sexuality research could have corresponding benefits, as would engaging in alternative forms of inquiry, including qualitative investigations (as is already beginning). This is particularly the case with research related to sexual behavior, identity, and intimate relationships, since these (for anyone) are complex phenomena where subjective experiences are meaningful. Exploring asexual people’s subjective realities will help researchers come to a better understanding not only of asexuality, but of sexuality more generally. Doing so through the use of qualitative methodologies will permit researchers to begin exploring the pervasiveness of the sexualnormativity12 that would otherwise remain invisible in sexuality-related research.”

Why sexual people don’t get asexuality and why it matters (A personal essay written by Mark Carrigan, an allosexual researcher of asexuality)

“ I had three initial aims with my asexuality research: mapping out community in a ideographically adequate way, understanding the role the internet played in the formation of the community and exploring what the reception of asexuality reveals about sexual culture. There’s still more I want to write in relation to the first two points but I’ve basically drawn my conclusions at this point. Which means that my interest in asexuality has basically transmuted into an interest in how sexual people react to asexuality. This sounds much more obscure than it actually is.

In essence I’m arguing that the reactions of sexual people to asexuality reveal the architectonic principle of contemporary sexual culture, namely the sexual assumption: the usually unexamined presupposition that sexual attraction is both universal (everyone ‘has it’) and uniform (it’s fundamentally the same thing in all instances) such that its absence must be explicable in terms of a distinguishable pathology. This is instantiated at the level of both the cultural system and socio-cultural interaction: it’s entailed propositionally, even if not asserted outright, within prevailing lay and academic discourses pertaining to sexuality but it’s also reproduced by individuals in interaction (talking about sex, either in the abstract or in terms of their own experience) and intraaction (making sense of their own experience through internal conversation).

Until the asexual community came along, the ideational relationship (the logical structure internal to academic and lay discourses about sex) and patterns of socio-cultural interaction (the causal structure stemming from thought and talk about sex) reinforced one another. Or to drop the critical realist terminology: the sexual assumption got reproduced at the level of ideas because nothing conflicted with it at the level of experience. But when something comes along which empirically repudiates it (namely the asexual community) the underlying principle suddenly becomes contested. This doesn’t mean discourse ‘makes’ sexual people not get ‘asexuality’ but it does mean that, given the centrality of the sexual assumption to our prevailing ways of understand sexuality, being confronted with asexuality immediate invites explanation. One such explanation is to drop the ideational commitment but, given that its usually tacit, few people (including myself) can do this immediately – though many, it seems, do so once they’ve reflected upon it. Instead the usual response is to evade the logical conflict by explaining away asexuality: its a hormone deficiency, the person was sexually abused, they’re lying, they’re gay but repressed, they’ve just not met the right person yet (etc).

The empirical evidence of quite how pervasive, indeed near universal, this kind of reaction is seems increasingly conclusive. What I am suggesting is that the sexual assumption is what explains this being a ‘kind’ of reaction i.e. all the explanations, in spite of their superficial differences in content, involve a reassertion of the uniformity and/or universality of sexual attraction. I’m not saying people are deliberately or consciously defending the sexual assumption (though I’m not categorically saying no one will ever be doing this) but rather that it is this, as the foundational assumption ‘holding together’ the conceptual architecture of the sexual culture which has emerged from the mid/late 20th century onwards, which asexuality renders problematic. The precise content of any given individual’s attempts to explain away asexuality varies depending on the specifics of their personal and intellectual history within this sexual culture (i.e. it’s not a homogenous thing) but the shared form of the response is explained by the architectonic principle of that culture and the logical relation of contradiction in which it stands to the empirical observation of asexual individuals who are ‘normal’ (i.e. non pathological). Logical relations don’t force people to act (some people don’t try and explain it away) but everyone who has not experienced what David Jay calls the ‘head-clicky thing’ has the same initial reaction. The above is my first attempt to offer a convoluted social theorists explanation of what I mean when, in interviews, I talk about sexual people not ‘getting’ asexuality. If you follow my chain of reasoning then, I ask of you, test it out: go and read the comments on the Guardian article I linked to and think about the reactions of people on there and what they have in common. Or do the same with pretty much any news article which has comments that I’ve encountered. There is something really fucking interesting happening there.”

A research programme for queer studies

“But it is (or at least, it should be) clear that an asexual person’s relationship, both logical and existential, with the categories of sexuality and gender is deeply different from that of, say, a bisexual person: a bisexual person could find it difficult to affirm their own definition of their sexuality in a num- ber of social situations and relationships, and could as a consequence be a victim of marginalization, discrimination or violence; but for an asexual person the category of sexuality is simply not relevant: to compel an asexual person to position themselves along this category is, quite simply, nothing but a new form of oppression: and this form of oppression is even more insidious than the one which dominant heteronormativity exerts towards sexual minorities. First of all, because it is paradoxically justified as a form of liberation; but most of all because the “orthodox” and the “deviants”, in the field of sexuality and gender as in all others, share at least an orientation towards the world and a definition of priorities; both the inquisitor and the heretic place faith and dogma at the core of their self-definition. But that a person for whom the category of sexuality has no relationship to their lived experience and self-perception should be offered, as a form of liberation, the possibility to “integrate” in, and “be represented” by, a movement defined by the centrality and productivity of the category of sexuality and of all experiences (both positive and negative) which arise from it, is more or less equivalent to offering a person with no interest whatsoever in soccer the possibility to “integrate in society” by “coming out” as a supporter of some team, and of attending their games every Sunday.“

Sexual Violence

Rape And Sexual Coercion

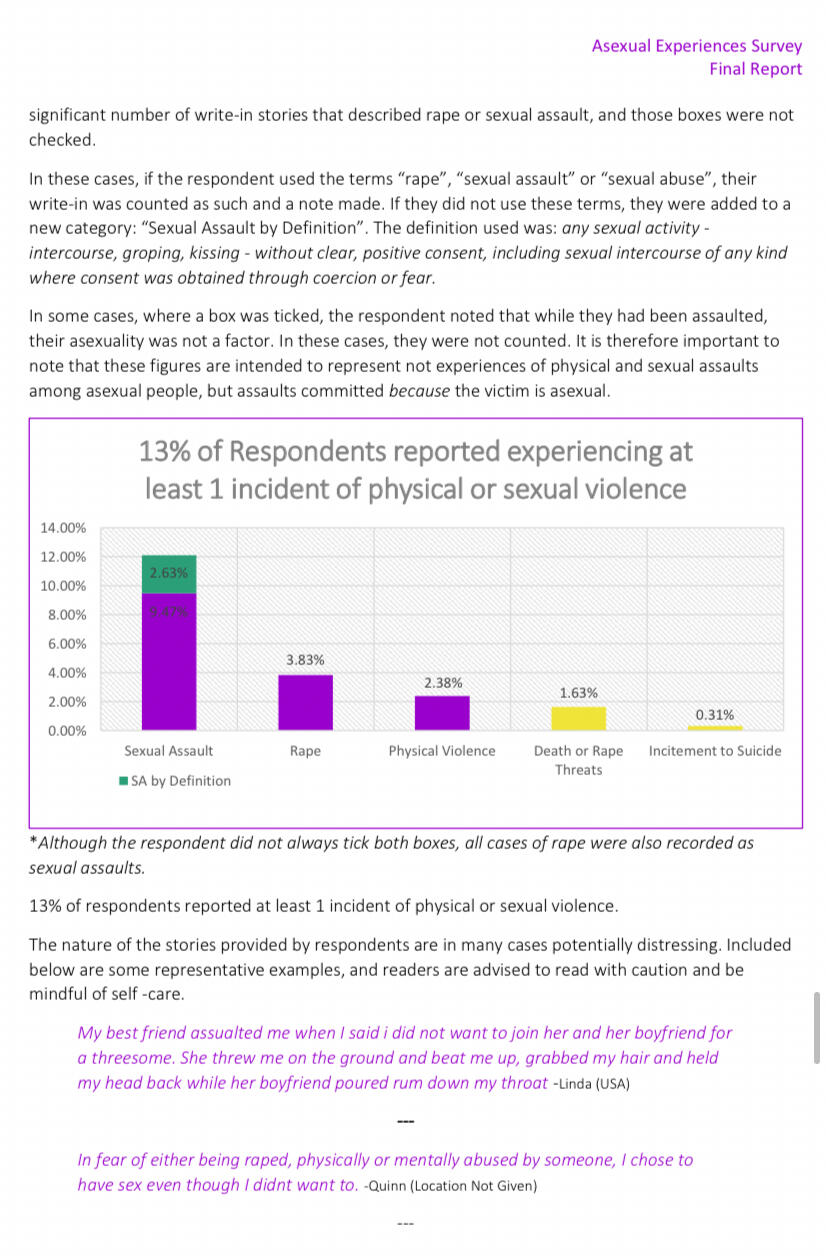

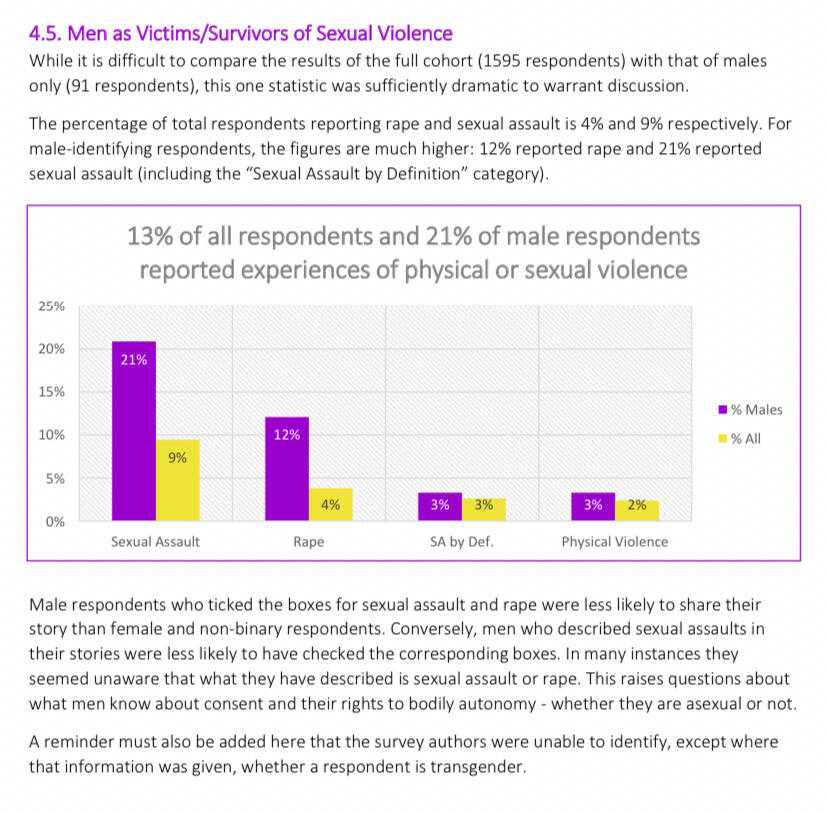

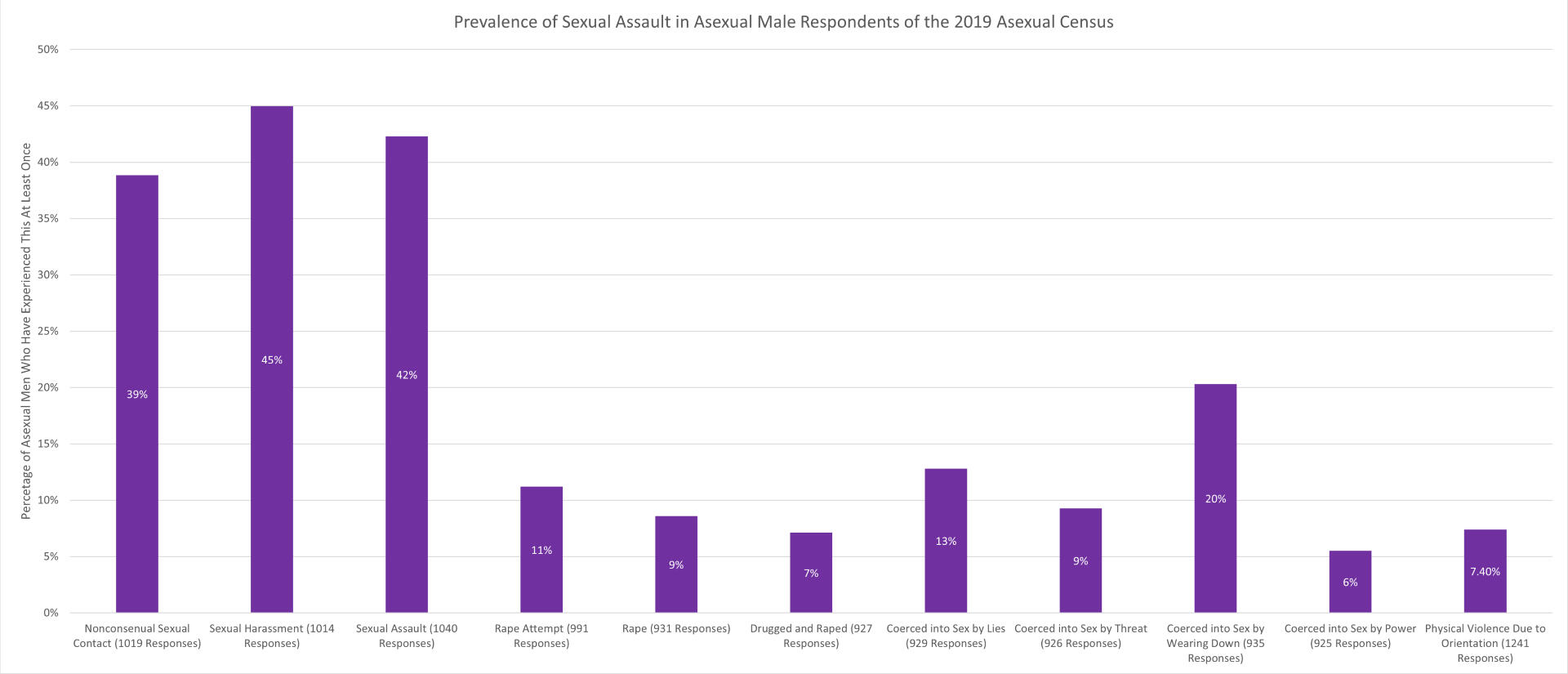

Although there has been numerous qualitative studies and a wide berth of anecdotal evidence illustrating that asexuals are disproportionally affected by sexual violence, there has yet to be a quantitative study that has evaluated exactly how prevalent it is within the community. The Asexual Census provides some clue, but there needs to be a peer-reviewed study before any conclusions can be drawn.All sources will be uploaded under the Works Cited page.Contact @asexualresearch on Twitter or [email protected] for articles that should be added, questions, or concerns!

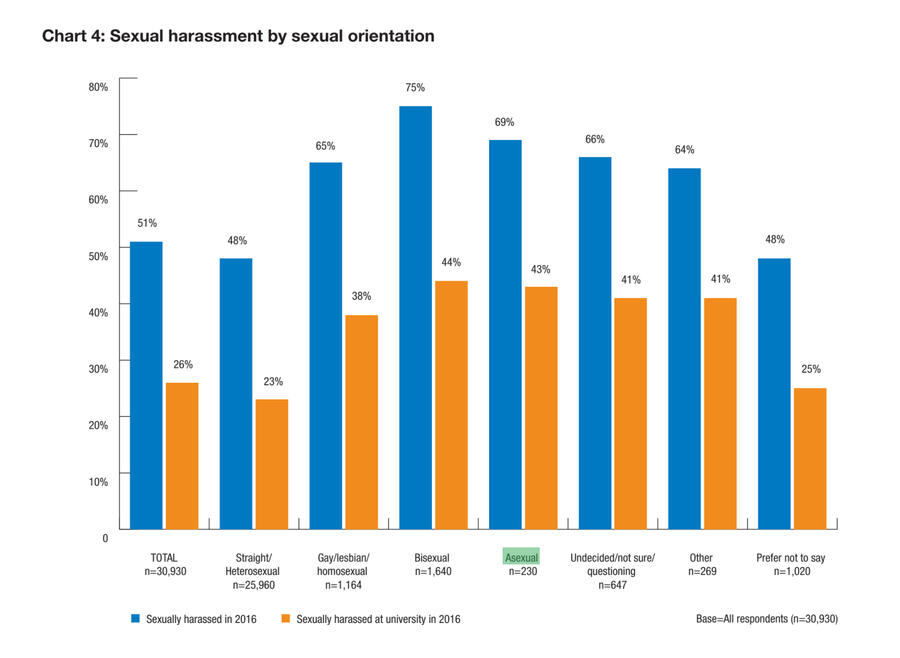

Change the course:

National report on sexual assault and sexual

harassment at Australian universities 2017

"When incidents occurring while travelling to or from university are excluded:

• 19% of students who identified as straight/heterosexual

• 34% of students who identified as gay/lesbian/homosexual

• 36% of students who identified as bisexual

• 38% of students who identified as asexual, and

• 36% of students who identified as undecided/not sure/questioning.

were sexually harassed in a university setting in 2016."

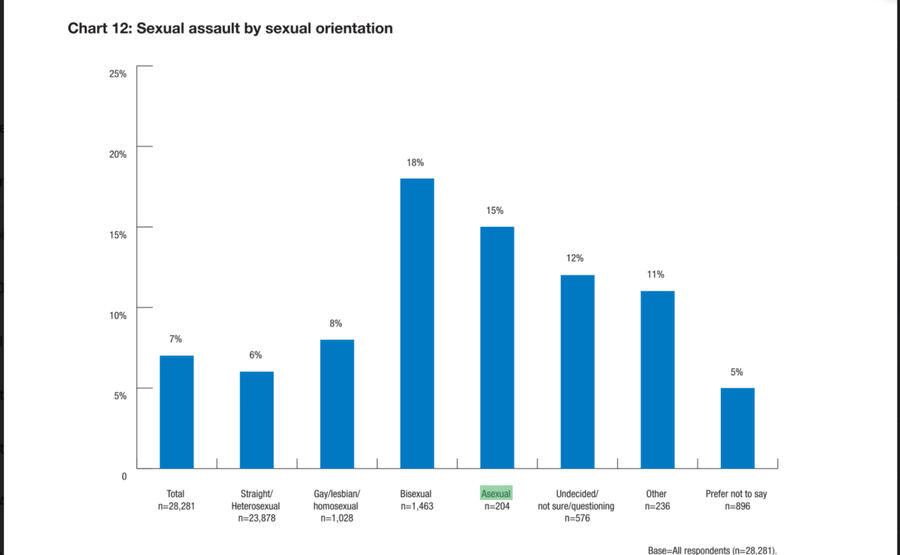

"Students who identified as bisexual or asexual were the most likely to have been sexually assaulted in 2015 and/or 2016.

Students who identified as bisexual (18%) or asexual (15%) were more likely than students who identified as gay/lesbian/

homosexual (8%) or heterosexual (6%) to have been sexually assaulted in 2015 and/or 2016.

Those who identified as bisexual (3.8%) were also more likely than those who identified as heterosexual (1.5%) or gay/

lesbian/homosexual (1.4%) to have been sexually assaulted in a university setting in 2015 and/or 2016."

A Note On The Small Sample Size:

"The following caveats apply to the National Survey results reported in this report:

1. The survey data has been derived from a sample of the target population who were motivated to respond, and

who made an autonomous decision to do so. It may not necessarily be representative of the entire university

student population.

2. People who had been sexually assaulted and/or sexually harassed may have been more likely to respond to this

survey than those who had not. This may in turn have impacted on the accuracy of the results.

3. People who had been sexually assaulted or sexually harassed may have chosen not to respond to the survey

because they felt it would be too difficult or traumatic. This may also have impacted on the accuracy of the results.

An independent analysis of the data was conducted in order to assess whether any ‘response bias’ existed in relation to

the survey, by examining the relationship between university response rates and the extent to which people said they had

experienced or witnessed sexual assault or sexual harassment.

‘Response bias’ can occur where people who had been sexually assaulted or sexually harassed are more likely to respond

to the survey than those who had not. Conversely, ‘non-response bias’ can occur where people who had been sexually

assaulted or sexually harassed chose not to respond to the survey because they felt it would be too difficult or traumatic.

Either of these can impact on the accuracy of the results.

This analysis found that universities with a higher proportion of survey respondents who said they had witnessed sexual

harassment at university in 2016 had higher response rates. This indicates that survey respondents who witnessed sexual

harassment in 2016 may have been more likely to respond to the National Survey.

An examination of the responses from men and women revealed that for men, there was a positive association between

response rates and experiencing or witnessing sexual assault or sexual harassment.

This indicates that men who had experienced or witnessed sexual assault or sexual harassment may have been more likely

to complete the survey. Therefore, caution must be taken in relation to our results which are projected to the population of

male students. These may be an overestimation of the rates of sexual assault and sexual harassment experienced by male

university students.

No such ‘response bias’ was identified in relation to women and we are therefore more confident in projecting these results

to the population of female university students."

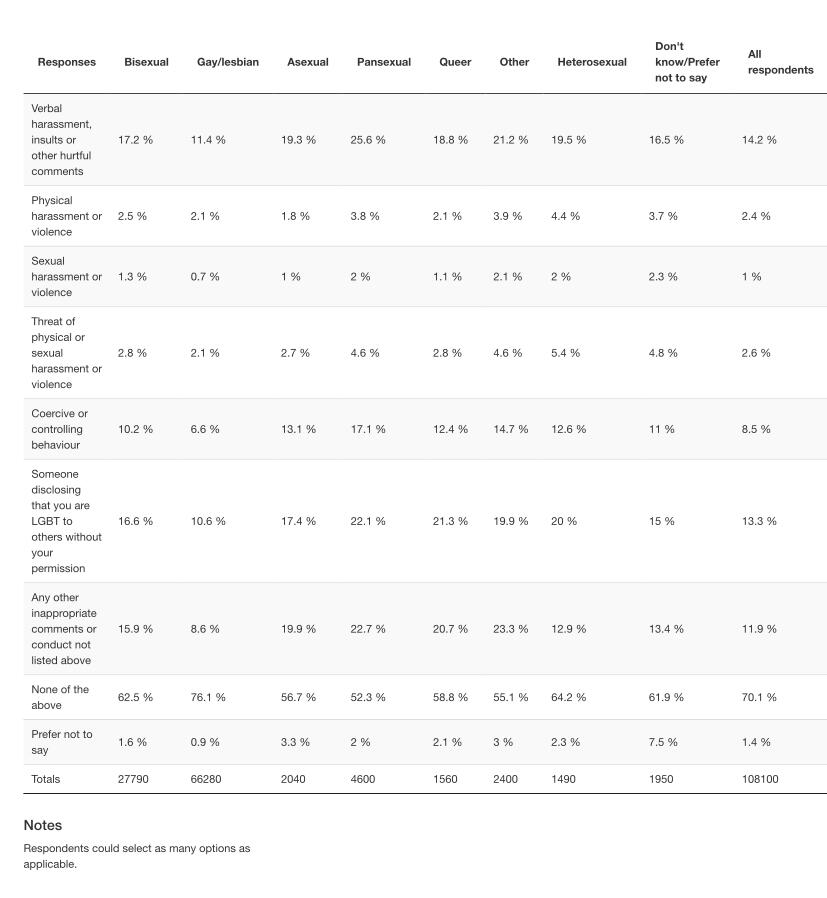

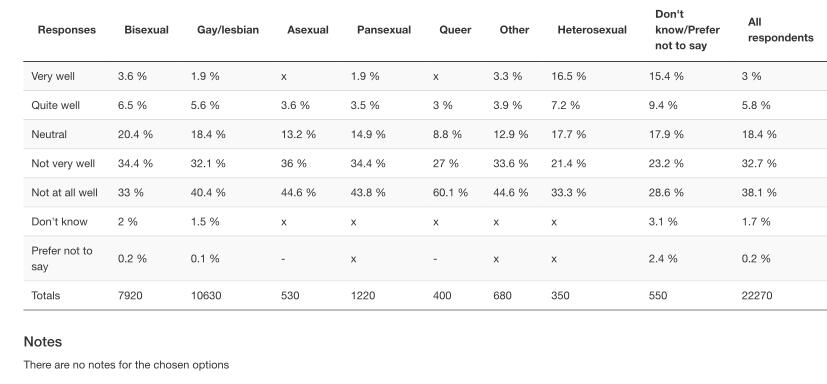

National LGBT Survey 2017 UK

The link above leads to the interactive data set. In the PDF library I have also included the analysis provided by researchers that the quotes arise from.

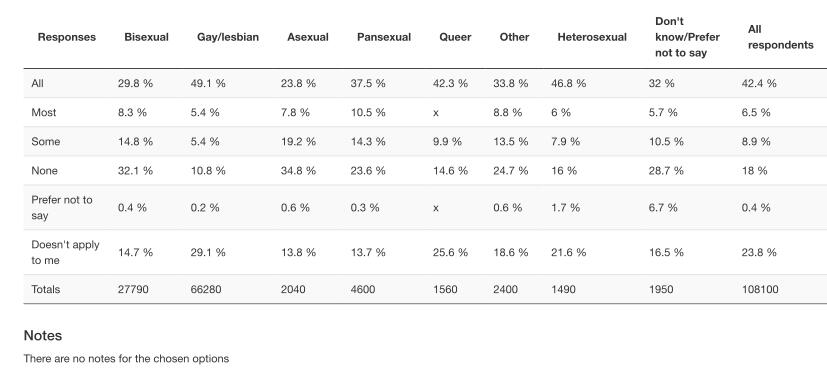

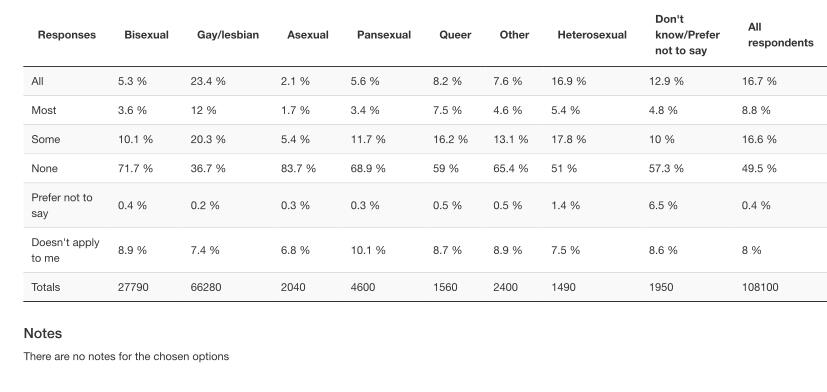

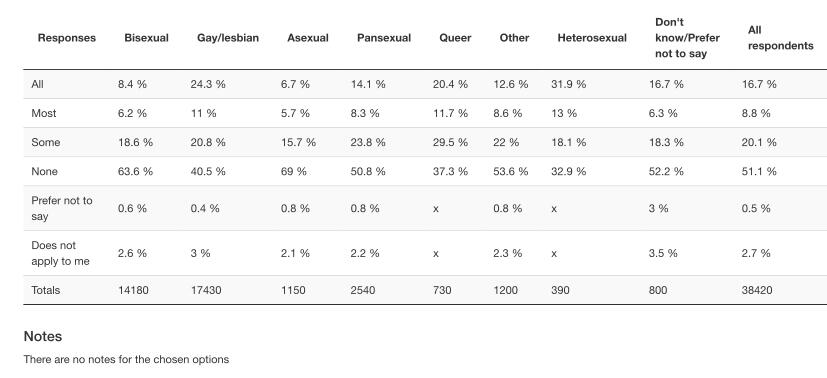

In the past 12 months, did you experience any of the following from someone you lived with for any reason?

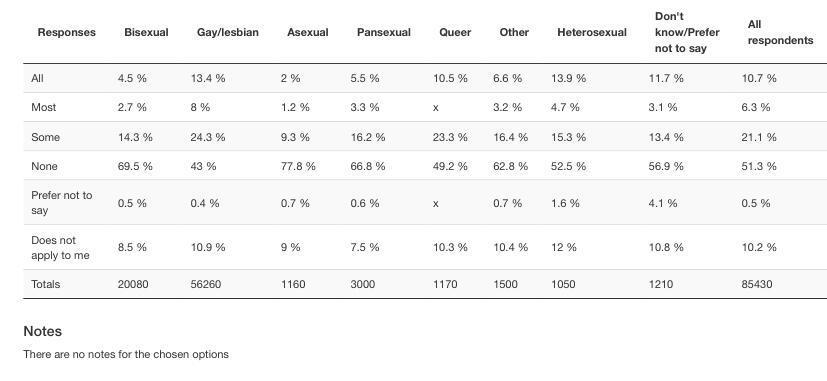

In the past 12 months, how many family members that you lived with, if any, were you open with about being LGBT?

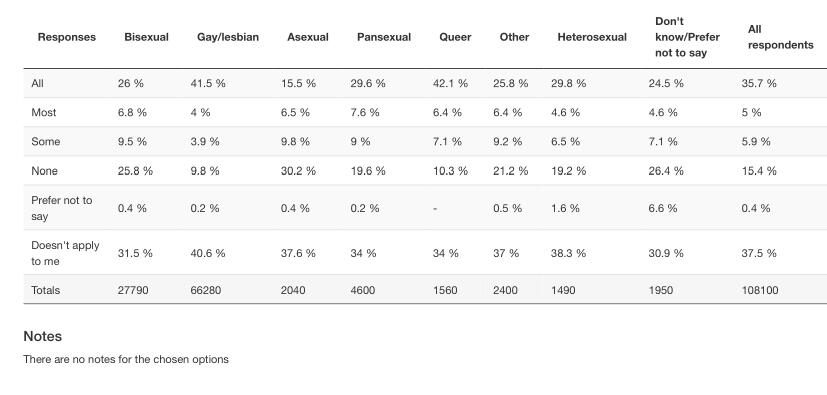

In the past 12 months, how many people you lived with, if any, were you open with about being LGBT?

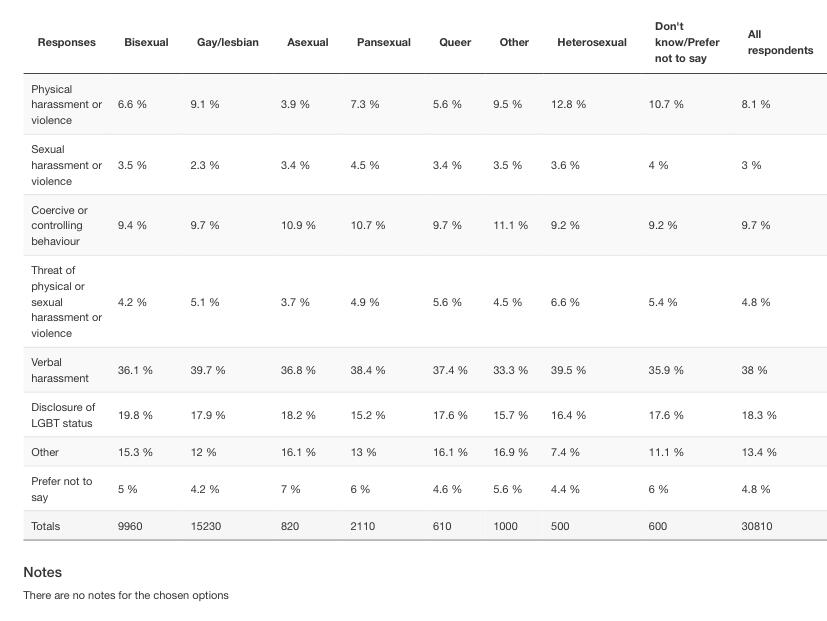

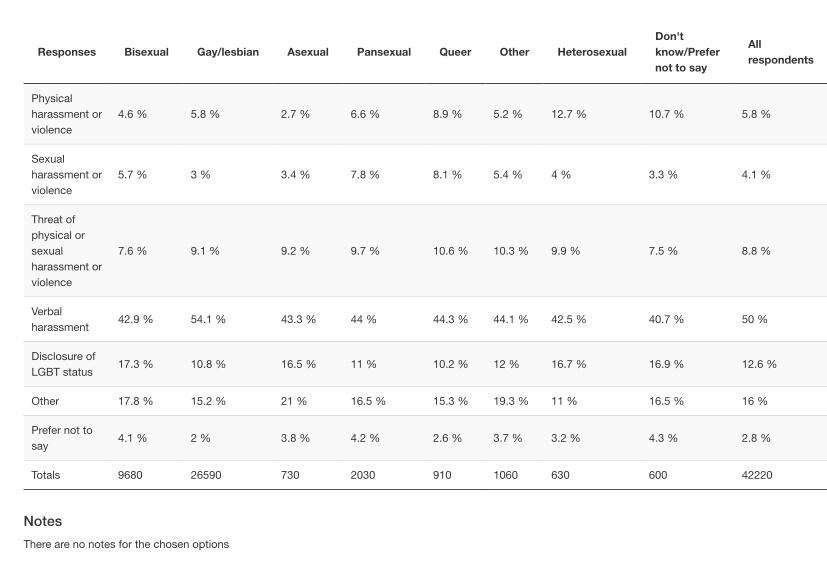

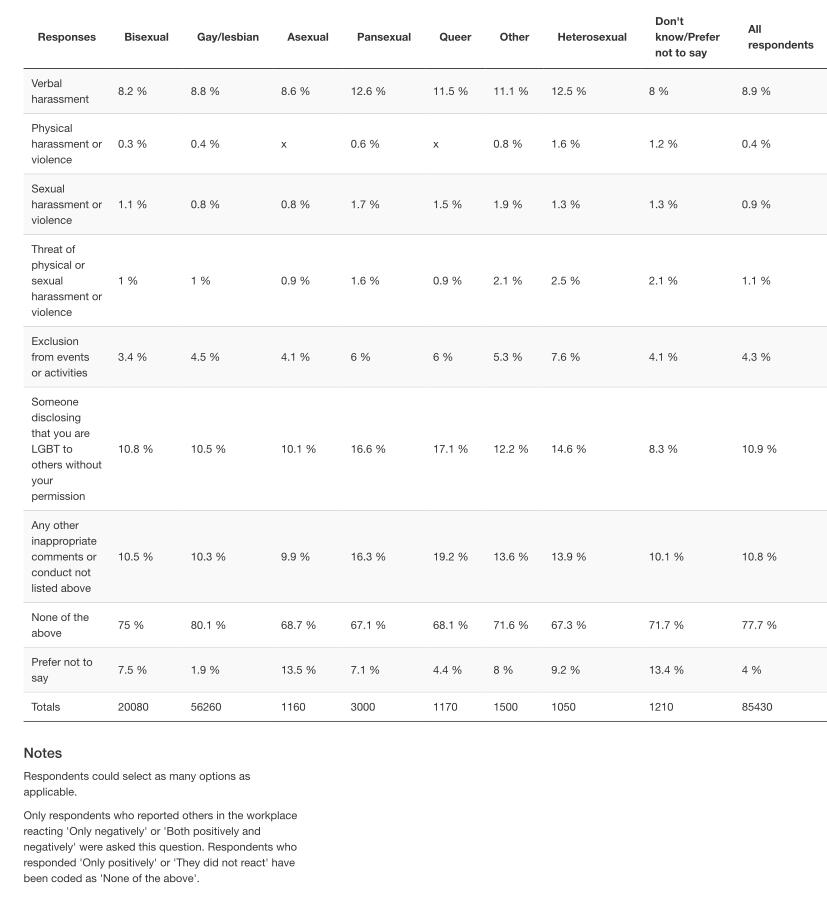

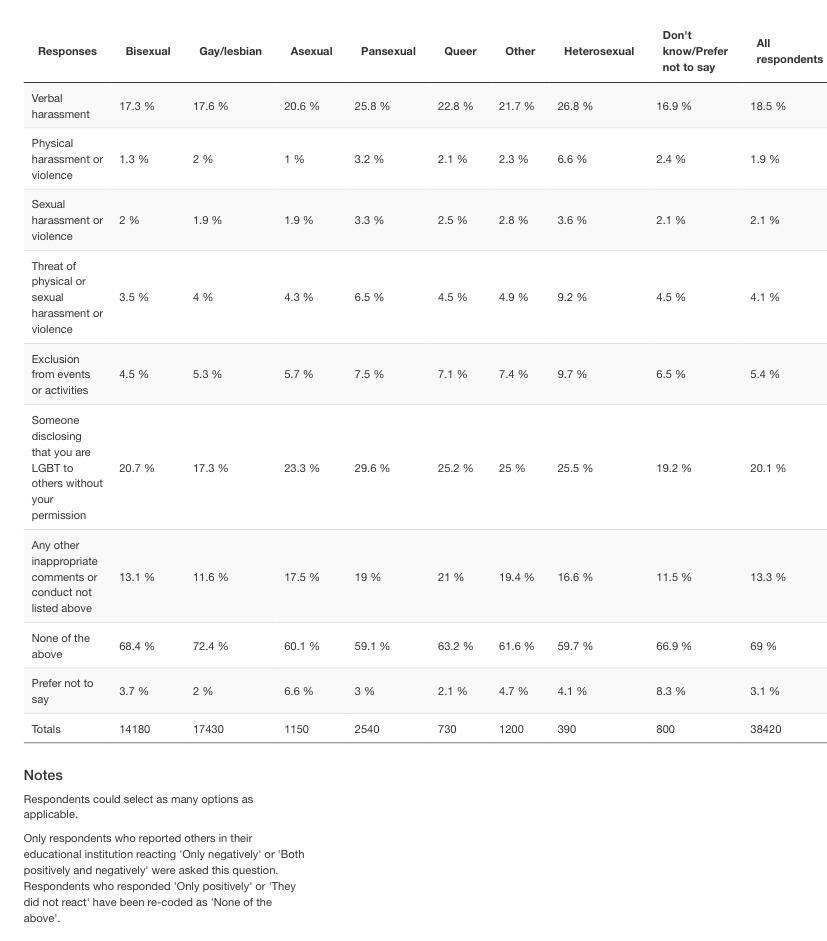

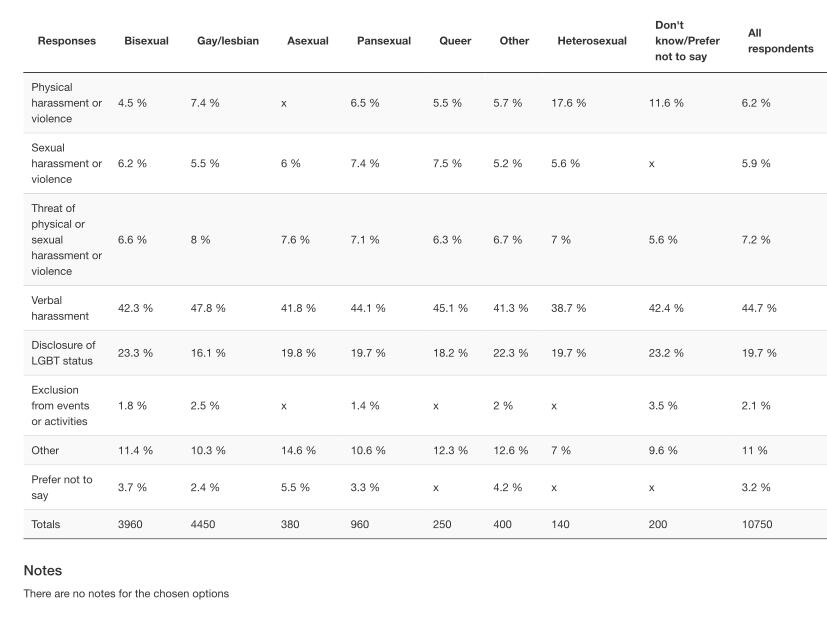

Think about the most serious incident in the past 12 months. Which of the following happened to you?

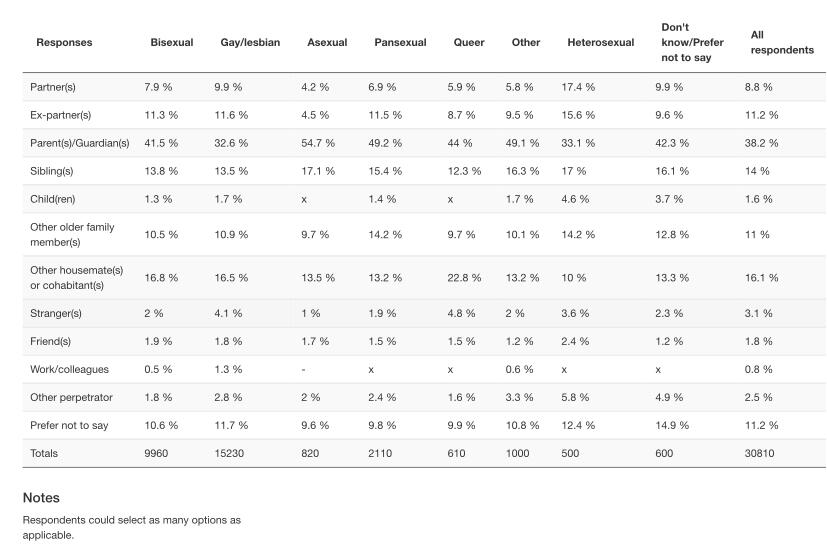

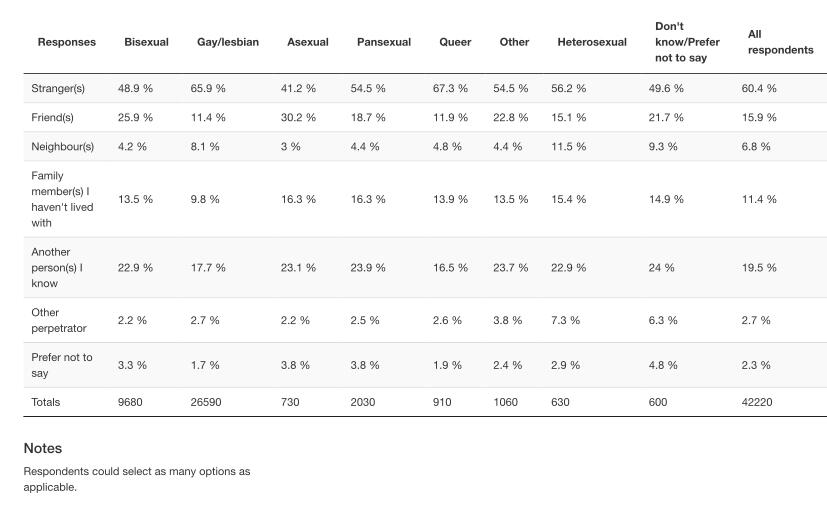

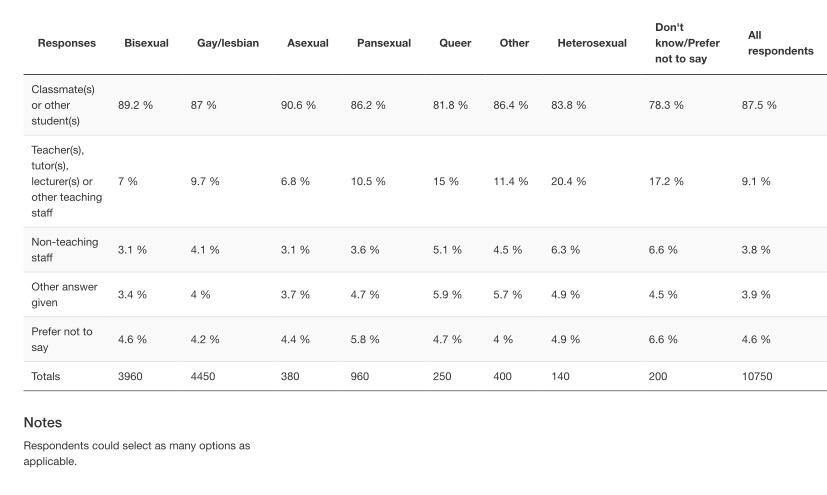

Who was the perpetrator(s) of this most serious incident?

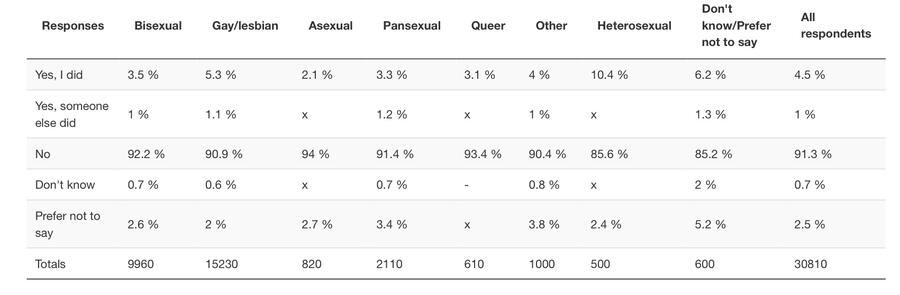

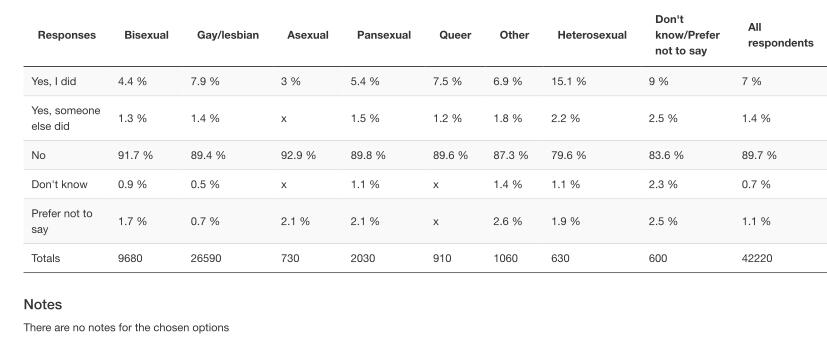

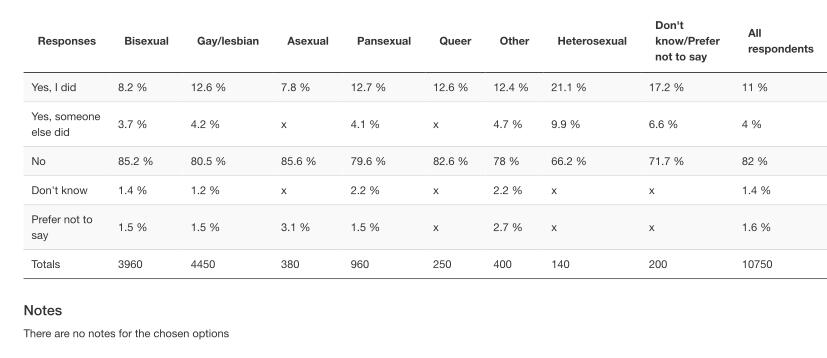

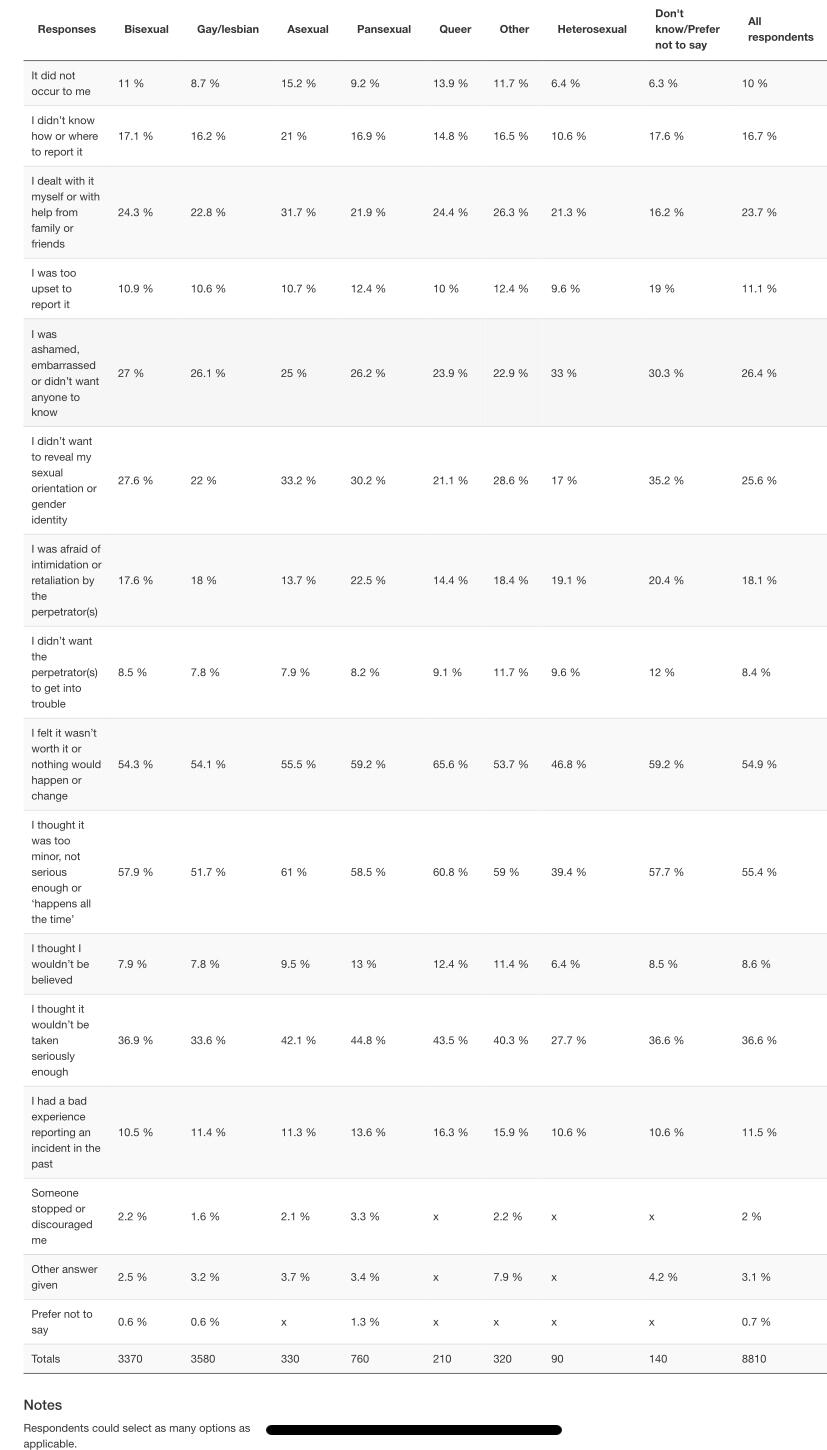

Did you report this most serious incident?

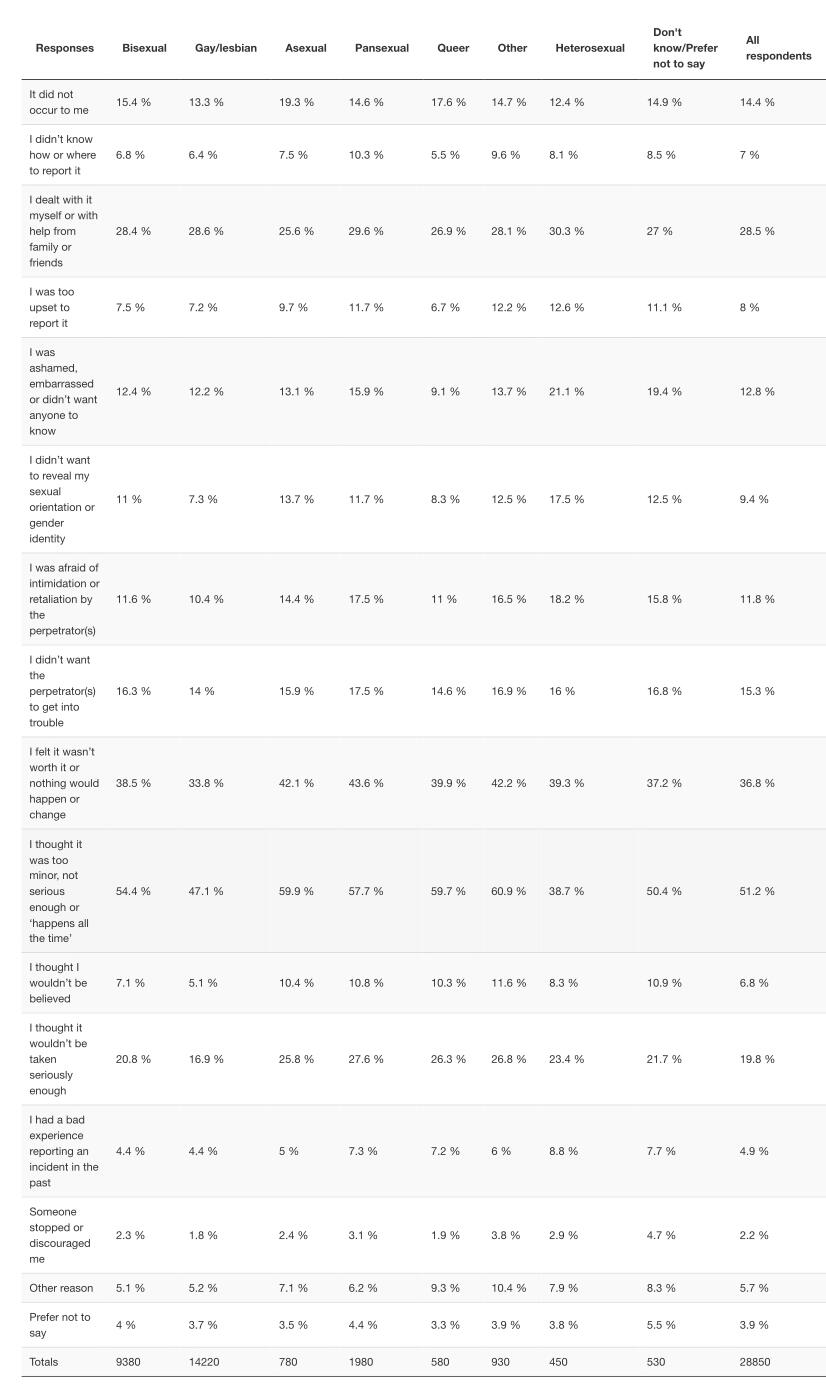

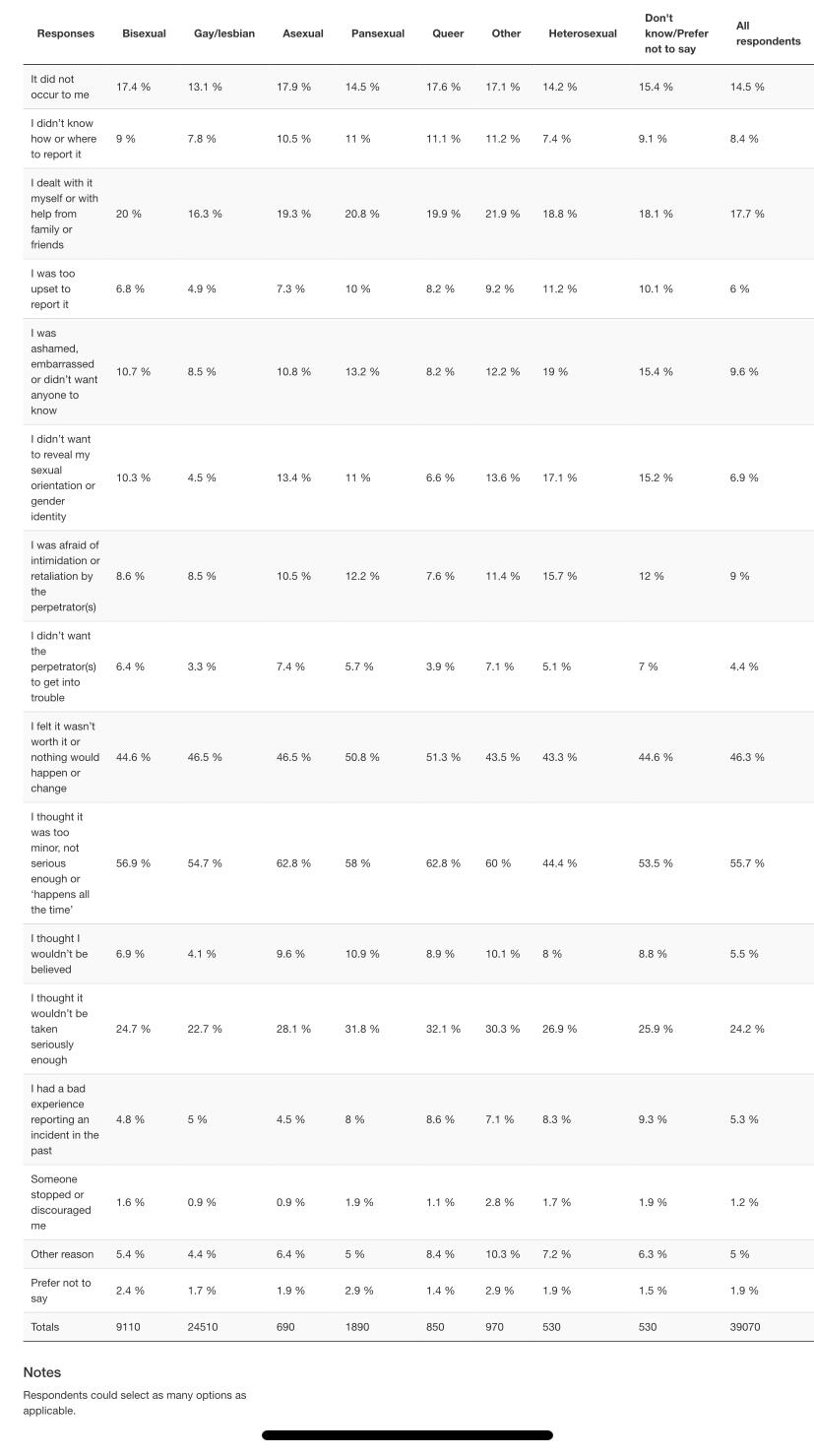

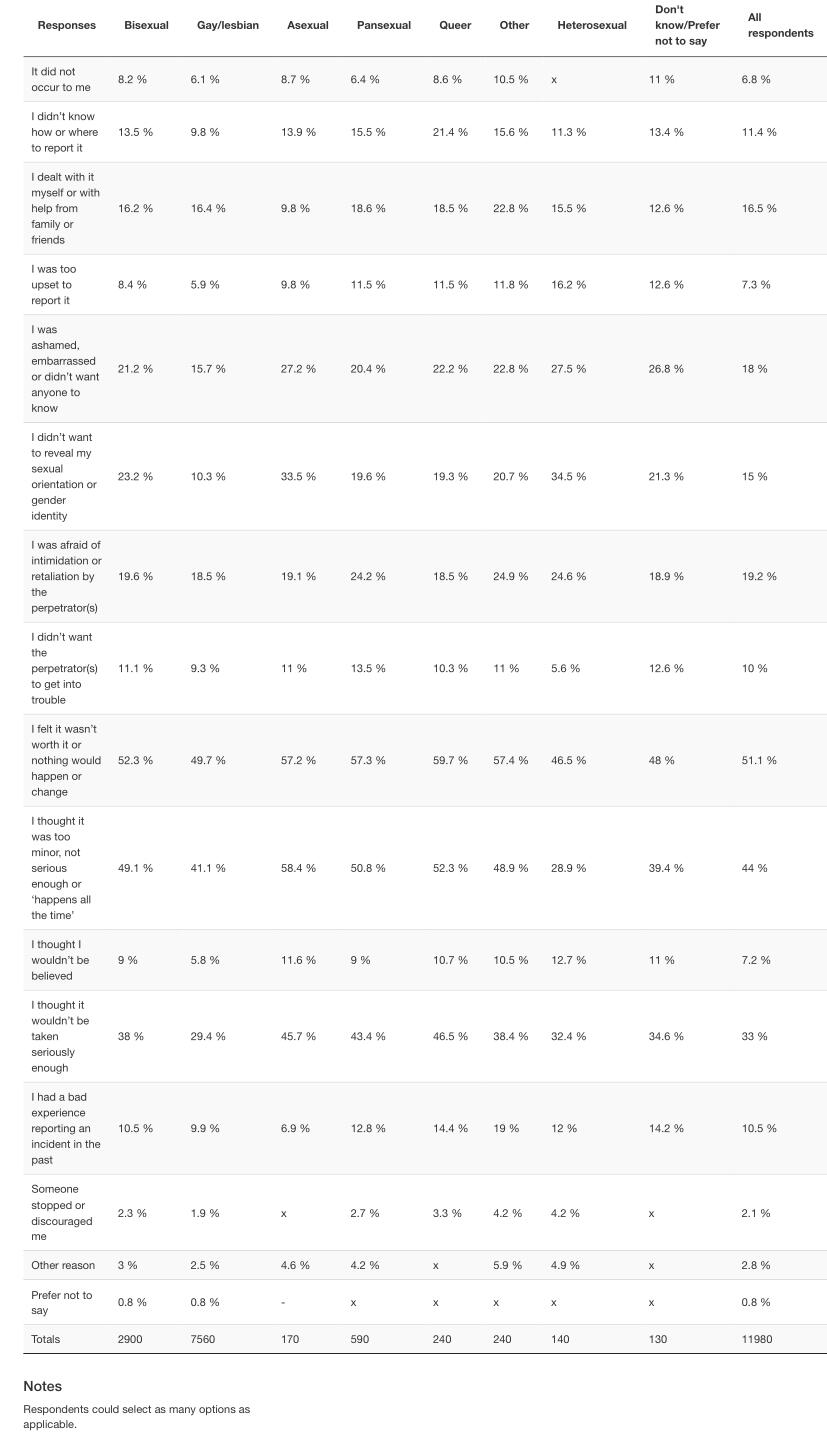

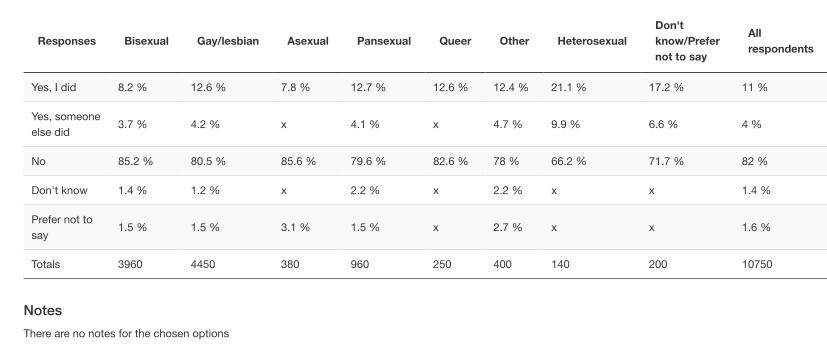

Why did you not report this most serious incident to the police?

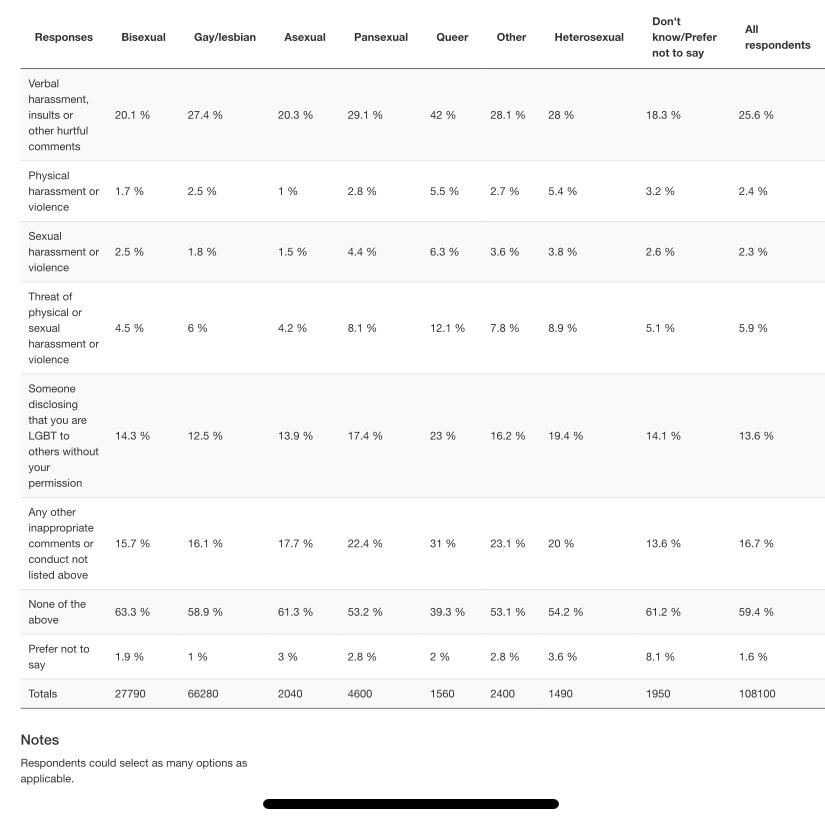

In the past 12 months, did you experience any of the following from someone you were not living with because you are LGBT or they thought you were LGBT? For example, from a friend, neighbour, family member you don't live, or a stranger. Please only include incidents that you haven't already told us about in this survey.

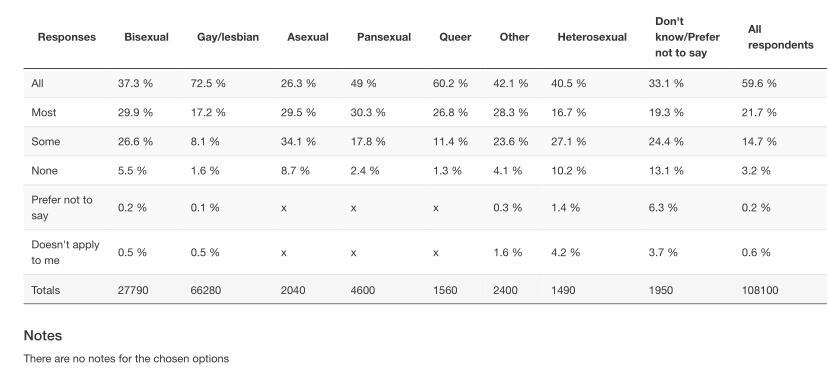

In the past 12 months, how many people in the following groups, if any, were you open with about being LGBT - Family members you were not living with?

In the past 12 months, how many people in the following groups, if any, were you open with about being LGBT - Friends you were not living with?

In the past 12 months, how many people in the following groups, if any, were you open with about being LGBT - Neighbours?

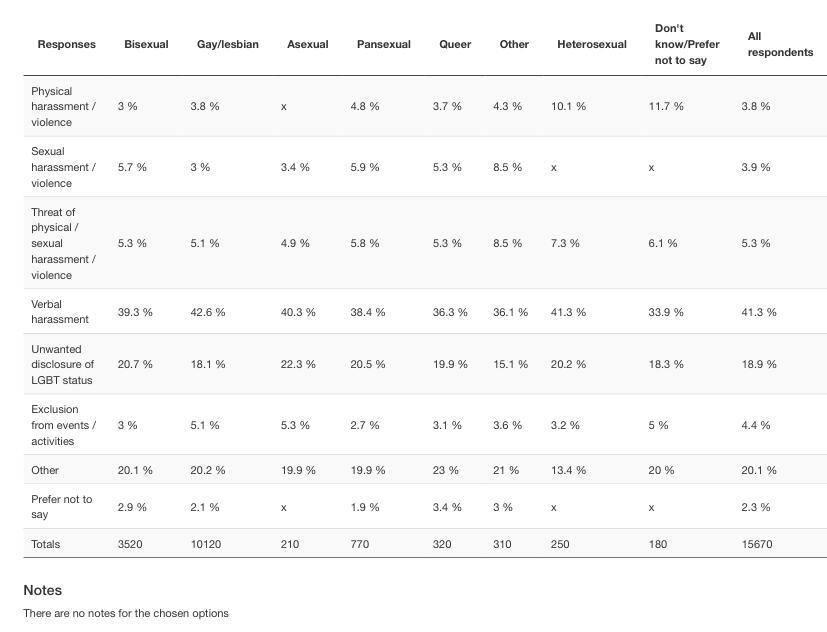

Think about the most serious incident in the past 12 months. Which of the following happened to you?

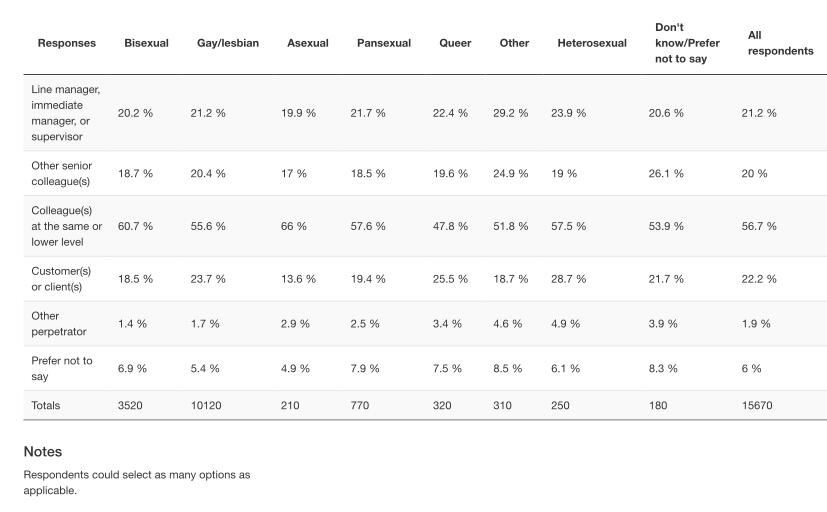

Who was the perpetrator(s) of this most serious incident?

Did you or anyone else report this most serious incident?

Why did you not report this most serious incident to the police?

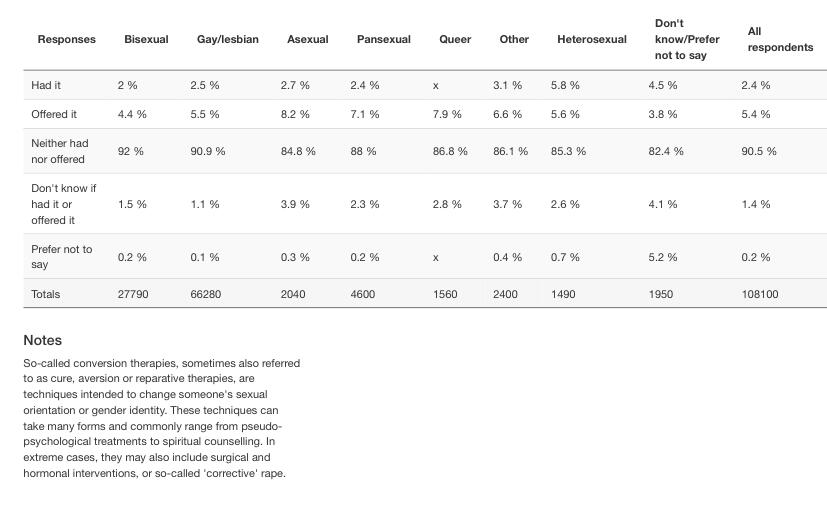

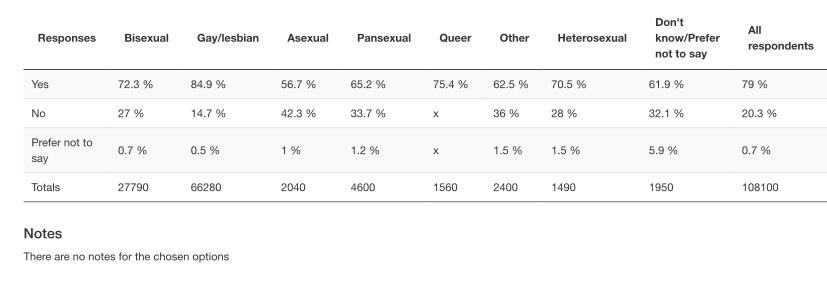

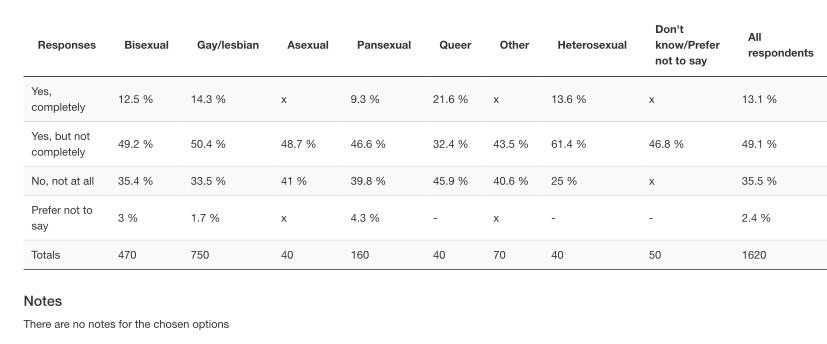

Have you ever had so-called "conversion" or "reparative" therapy in an attempt to "cure" you of being LGBT? Have you ever been offered this so-called "conversion" or "reparative" therapy? (*the study included corrective rape under this section, see note under each table)

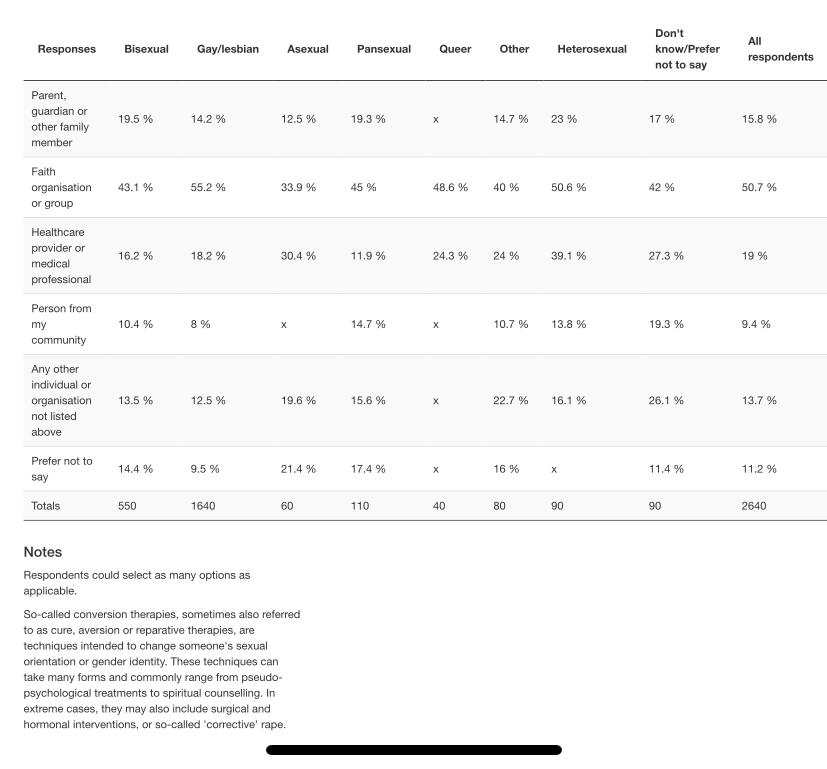

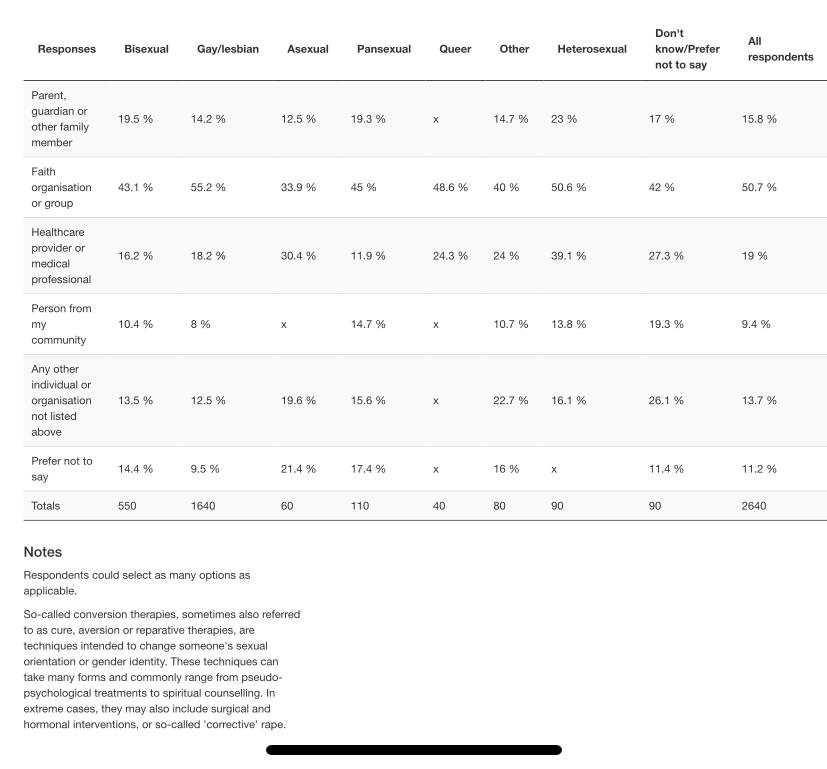

Who conducted this so-called "conversion" or "reparative" therapy?

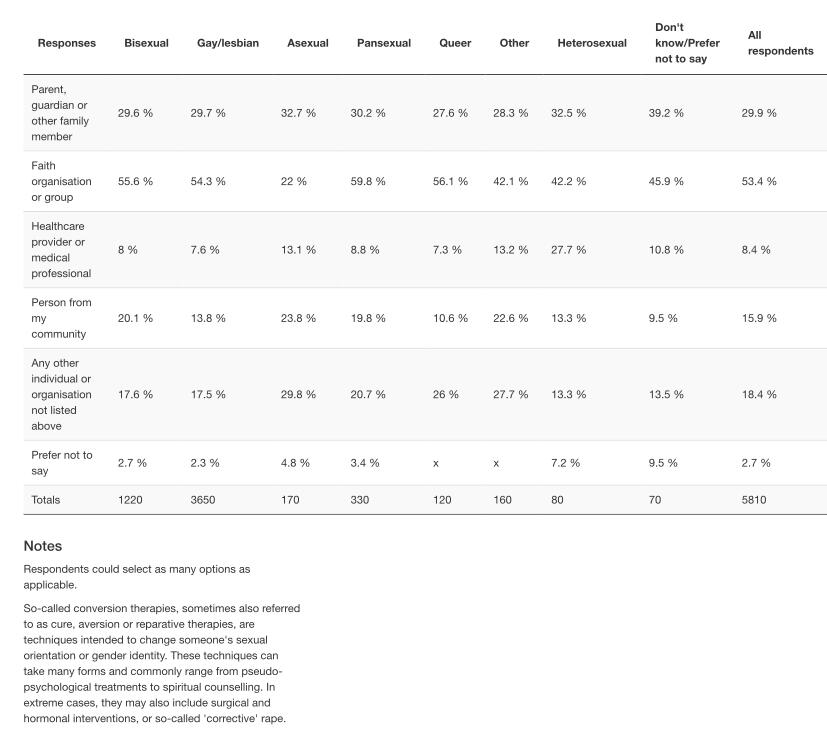

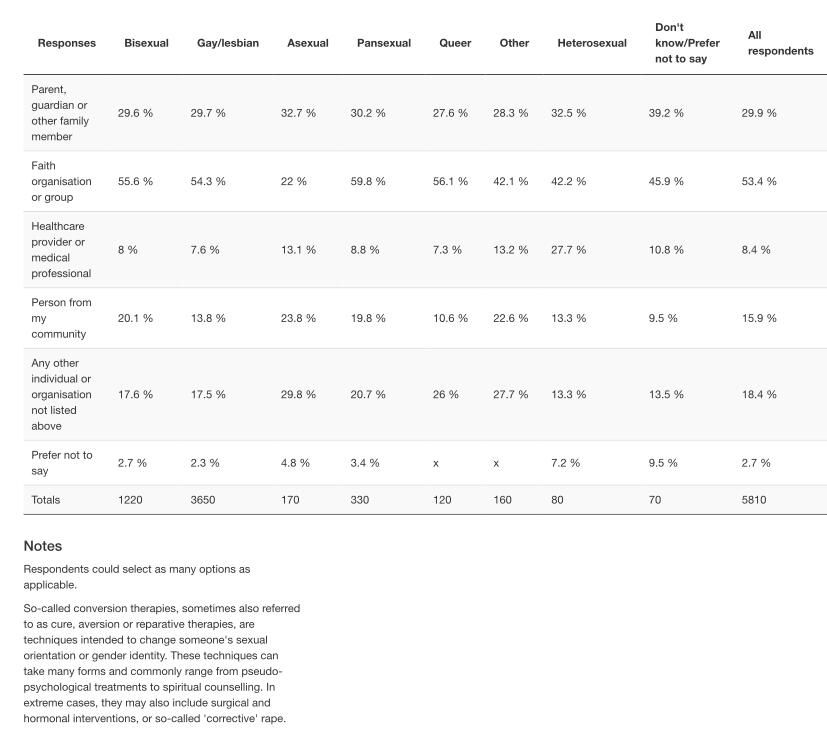

Who offered this so-called "conversion" or "reparative" therapy?

ACT Aces: Asexual

Experiences Survey

Handbook of Sexual Assault and Sexual Assault Prevention

The 2015 Asexual Community Census (N = 8663 people on the asexual spectrum, including asexual, demisexual, or graysexual) found similarly alarming rates of lifetime sexual violence victimization among asexual individuals, 43.5% of whom reported rape or sexual assault (Bauer et al., 2017).

2019 Ace Census

A STUDY OF TRENDS OBSERVED IN SELF- IDENTIFIED ‘ASEXUAL’ PEOPLE (A study that took place in India that was presented at the 23rd Congress of the World Association for Sexual Health)

“While 12% of the total reported having a medical/physical condition, 40% reported being diagnosed with mental conditions such as depression/

anxiety/PTSD/personality disorders etc. 15% of all reported a history of sexual abuse with or without PTSD.”

Expanding Use of the Social Reactions Questionnaire among Diverse Women (U.S. Department of Justice)

"To test links between the social reactions from community-based providers and

women’s decisions to report to law enforcement, we focused on a subset of 213 women who had

disclosed the sexual assault to a community-based provider (190, or 89%, of whom had also

disclosed to an informal support person). About half of women (119, 56%) had reported the

sexual assault to law enforcement, while 91 (43%) women had not. Chi-square analyses tested

associations between reporting (yes/no) and demographic as well as sexual assault

characteristics, revealing trends for sexual orientation (such that lesbian/bisexual/asexual were

less likely to have reported) and sexual coercion (such that women whose assaults involved

sexual coercion were less likely to report). Also, a trend suggested that women who reported had

greater fear related to the assault. Given these trends, sexual orientation, sexual coercion, and

fear were included in two binary logistic regression analyses that examined the contributions of

social reactions from 1.) community-based providers, and 2.) informal supports to whether

women had reported the assault to law enforcement."

Corrective Rape: An Extreme Manifestation of

Discrimination and the State’s Complicity in Sexual Violence (Hastings Women's Law Journal)

"Another population that is subjected to corrective rape is asexual

women.52 Asexuality—an identity for a person who does not experience

sexual attraction53—is an emerging concept in our society. Though it has

become increasingly normalized throughout the last few decades to have an

open attitude around sexuality,54 discussion of asexuality has been largely

ignored until recently.55 Research and discourse on asexuality have been

naturally overshadowed by the more prominent and more common sexual orientations—heterosexuality, homosexuality, and bisexuality.56

An unfortunate consequence of this inattention is that we have

overlooked the harm and threats that an asexual person faces. For instance,

one would not expect that an asexual individual would be the target of

prejudice and discrimination.57 After all, asexuality is marked by the absence

of something (i.e., sexual attraction, and often sexual behavior), and has thus

been characterized as “the least visible sexual minority.”58 In addition,

asexual individuals pose no sexual risk, they do not flaunt their participation

in deviant practices, they do not violate religious prohibitions in the way

homosexual or bisexual individuals have been condemned for, and, as a

group, they do not require any kind of costly accommodation.59 Taken

together, these facts would instinctively lead one to conclude that asexual

people would not be the target of animus, hostility, bias, and discrimination.

However, “outgroup hate” plays a central role in human beings’ social

identities.60 In a 2012 study, researchers revealed strikingly strong bias

against asexual people.61 Predictably, attitudes towards homosexual,

bisexual, and asexual people were more negative than attitudes toward

heterosexual people.62 The more groundbreaking result was that within

sexual minorities, asexual people were evaluated most negatively of all

groups, falling behind both homosexual and bisexual people.63 Further, of

all the sexual minority groups studied, asexual people were perceived to be

the least “human;” they were attributed with significantly fewer human

nature traits and were perceived to experience fewer human emotions.64Asexual people are dehumanized by being characterized as both “machine-

like” and “animal-like.”65 Because sex is so much a part of non-asexualpeoples’ lives, and because of the pervasive sexualization of our society,

those who reject sex are viewed as less than or not even human.66

As attention has increased towards asexuality, animosity towards asexual people has increased correspondingly.67 Beyond discrimination, the

most extreme form of this animus is sexual violence designed to eradicate

asexuality.68 Asexual activist Julie Decker reported that sexual harassment

and violence, including corrective rape, is disturbingly familiar to the

asexual community.69 She stated that people who carry out corrective rape

do so because “they believe that they’re just waking us up and that we’ll

thank them for it later.”70 Decker has received death threats and numerous

comments that she “just needs a ‘good raping’”—leading her to conclude

that when some people hear that a person is asexual, they see it as a

challenge.71 In recounting the sexual assault she personally experienced,

Decker said that after speaking extensively about her asexuality with a

friend, he tried to “fix” her by sexually assaulting her.72 She recalled that he

tried to kiss her, and when she rejected his advance, he pushed her against

the door, licked her face, and yelled, “I just want to help you!”73

Similar instances of corrective rape are seen in case law. For example, in

State v. Dutton, the complainant had approached a pastor to discuss her

emotional and psychological issues in counseling, including low self-esteem,

suicidal thoughts, grief over her daughter’s death, and her eating disorder.74

Though she had stated her desire to be asexual and to keep their relationship

platonic, the pastor persisted in discussions about sex, and told her that he

would be “‘working’ with her on her sexuality.”75 He subsequently engaged

in criminal sexual conduct with her multiple times, asserting that this sexual

conduct was “consistent with her treatment” because it would “remove her

inhibitions about sex.”76 He told her that sexual contact would “set her free”

and that he knew that she was “hung up” sexually.77 Though the pastor

claimed he had a right to engage in consensual sexual activity with another

adult, the complainant was a counseling patient unable to withhold consent to

sexual contact by her therapist.78"

The Co-Occurrence of Asexuality and Self-Reported Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis and Sexual Trauma Within the Past 12 Months Among U.S. College Students (Archive of Sexual Behavior)

This is one of the few articles I don’t have a full copy of. I’ve linked to the abstract, of someone has access to it I would love the PDF!

“An increasing number of individuals identify as asexual. It is important to understand the relationship between a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder or a history of sexual trauma co-occurs with asexual identity. We aimed to assess whether identification as asexual was associated with greater likelihood for self-reported PTSD diagnosis and history of sexual trauma within the past 12 months. Secondary data analysis was undertaken of a cross-sectional survey of 33,385 U.S. college students (12,148 male, 21,237 female), including 228 self-identified asexual individuals (31 male, 197 female), who completed the 2015-2016 Healthy Minds Study. Measures included assessment of self-report of prior professional diagnosis of PTSD and self-report of prior sexual trauma in the past year. Among non-asexual participants, 1.9% self-reported a diagnosis of PTSD and 2.4% reported a history of sexual trauma in the past 12 months. Among the group identified as asexual, 6.6% self-reported a diagnosis of PTSD and 3.5% reported a history of sexual assault in the past 12 months. Individuals who identified as asexual were more likely to report a diagnosis of PTSD (OR 4.44; 95% CI 2.32, 8.50) and sexual trauma within the past 12 months (OR 2.52; 95% CI 1.20, 5.27), compared to non-asexual individuals. These differences persisted after including sex of the participants in the model, and the interaction between asexual identification and sex was not significant in either case. Asexual identity was associated with greater likelihood of reported PTSD diagnosis and reported sexual trauma within the past 12 months. Implications for future research on asexuality are discussed.“

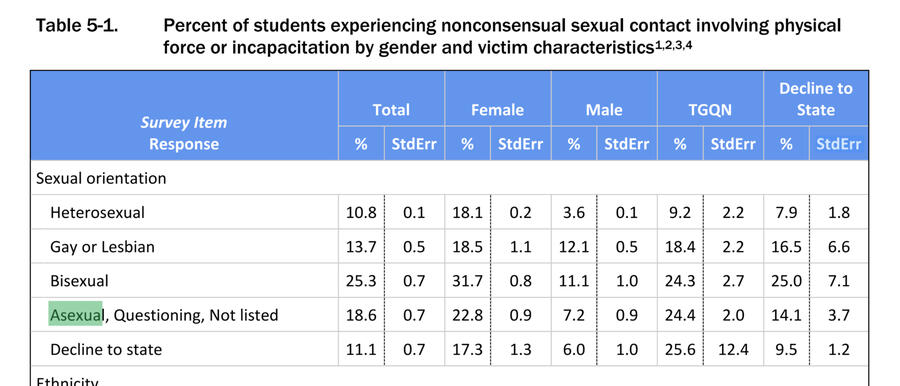

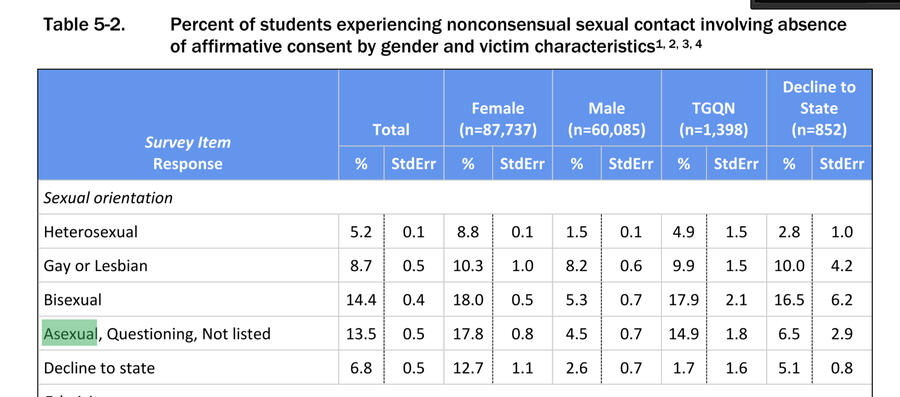

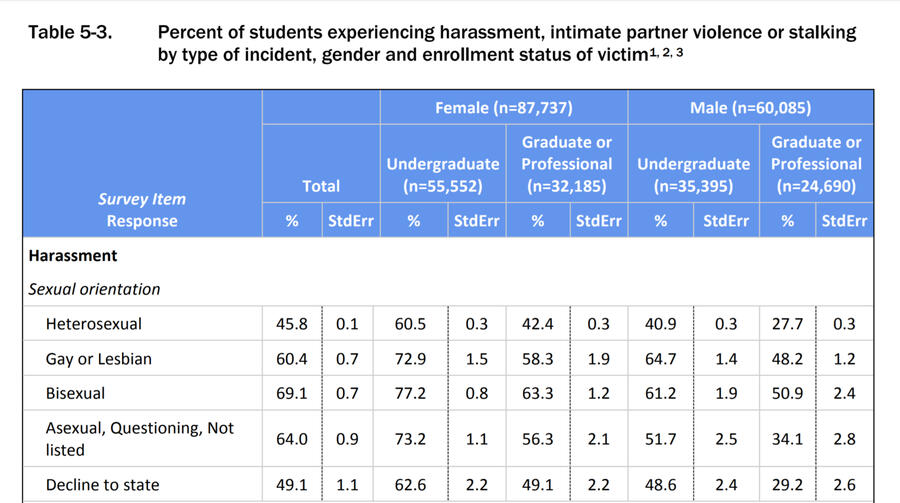

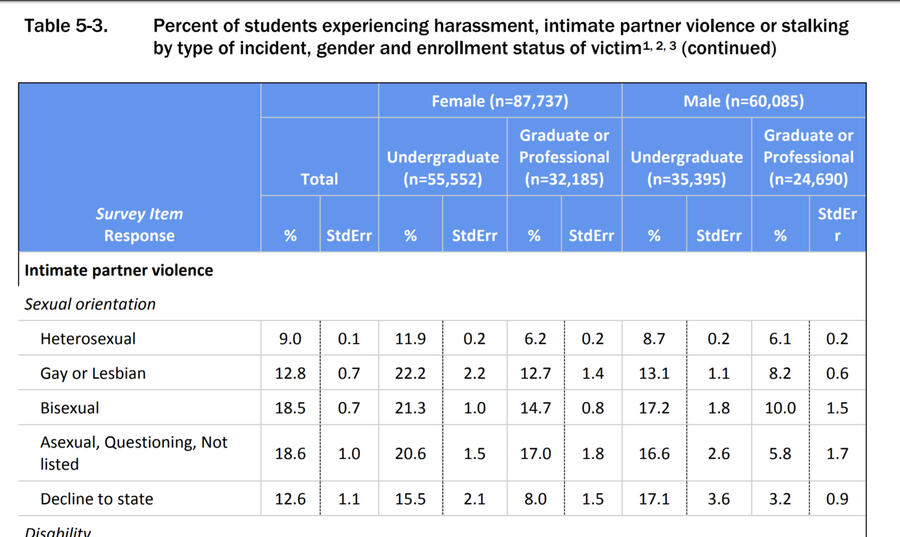

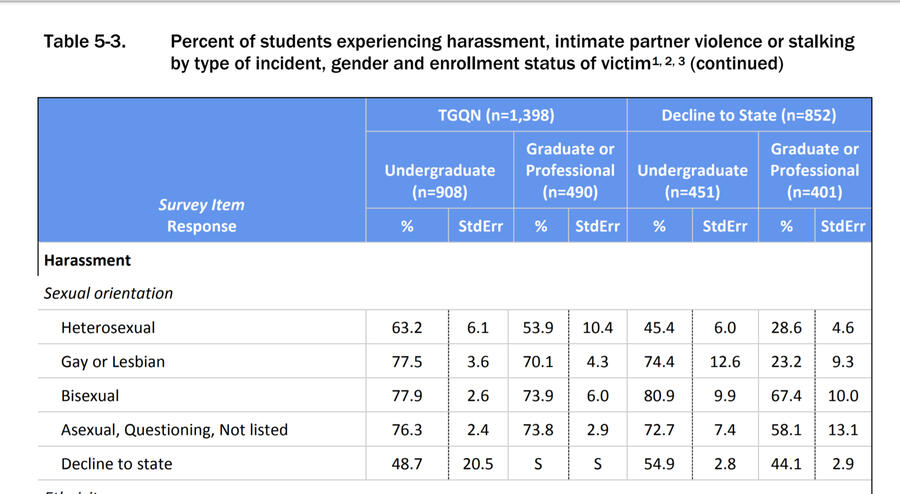

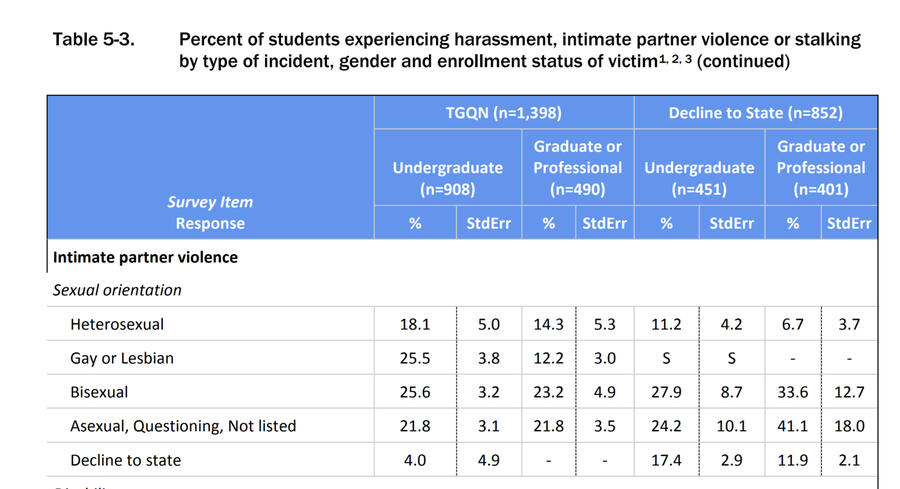

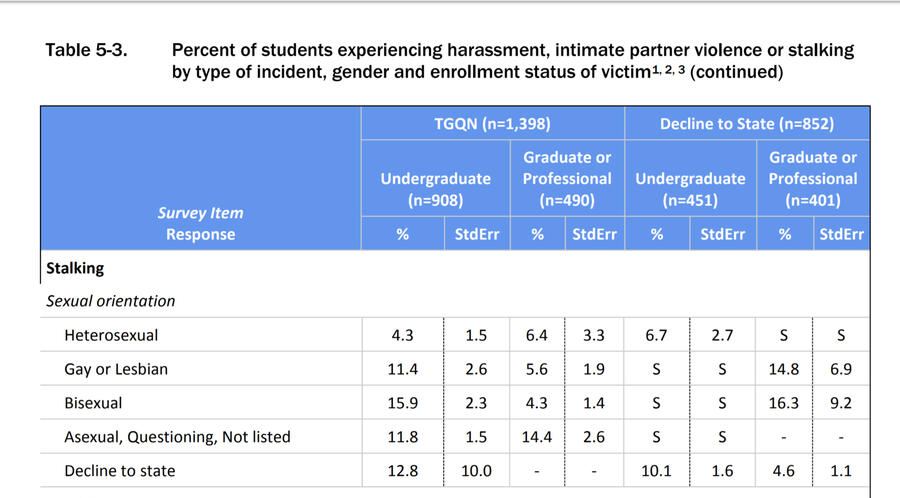

Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on

Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct 2017

An important note on this source: The results of the study grouped Asexual, Questioning, and Other together, so take the data with a grain of salt.

A is Not for Ally: Affirming Asexual College Student Narratives (University of Vermont)

It should be noted that some asexual people who want to engage in romantic and/or sexual relationships may also experience difficulty and violence within these relationships, especially if their partner is not asexual. One asexual and heteroromantic-identifying person, Idra, explained her frustration in being unable to be fully honest with her non-asexual partner about her asexuality:

Having sex is something that we do because I succumb to peer pressure and want to be normal, so I go ahead with it. I just wish that I knew how to approach the subject with him and then even know what to say if I did. (McDonnell, Scott, & Dawson, 2017)

The aforementioned misunderstandings that many non-asexual people hold about asexuality, if they even know about it at all, has the potential to cause serious issues in relationships. Such issues often materialize as non-asexual partners becoming frustrated because they do not understand the motivations asexual people may have to engage in sexual behavior, or that some asexual people who do engage in sexual behavior might be comfortable with some sexual acts but not others.

Beyond misunderstanding, asexual people often face intimate partner violence and sexual assault. Instances of corrective rape in which an asexual person is sexually assaulted in an attempt to “fix” or “convert” them are alarmingly common, especially those instances in which cishet people, especially men, see asexuality as a challenge to their ability to seduce (Deutsch, 2018). The violence that asexual people experience related to their identity needs to be taken into consideration when reflecting upon and acting to improve the collegiate experience for asexual

students. Asexual students may enter the college environment already carrying trauma which may be attributed to their asexual identity.

Personal Agency Disavowed: Identity Construction in Asexual Women of Color (American Psychological Association)

“Identifying with a community supports the resolution of disso- nance (Carrigan, 2011), loneliness (Scherrer, 2008), and identity- related challenges (MacNeela & Murphy, 2015). Asexual people who have yet to find a community of like others may experience more isolation, distress, and confusion than members of other sexual identity groups (Brotto & Yule, 2009). Participants reported feelings of disconnection from their immediate peer groups, but significant connection with asexual groups online. The “birth” of asexuality as a social phenomenon on the Internet has been cred- ited as an important factor in allowing this population to grow (Scherrer, 2008). The Internet’s role in building community and helping people develop a communal identity is well documented in the literature (Carrigan, 2011; Pacho, 2013).

Stigma and visibility. As women, participants felt that they were subject to objectification, harassment, and gendered stereotypes. For example, participants described their physical appearance as “curvy,” “feminine,” and “attractive,” which made them feel more likely to be sexually propositioned. Being hypersexualized coincided with presumed accessibility as an object of sexual desire. In two cases, coercion and attempted sexual assault were discussed as conse- quences of objectification. Although one person shared that disclosing their asexuality was helpful in warding off advances, another person was accosted as a result of the same action. Findings align with much of the literature on WOC across sexual identities (Bowleg, 2008;

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.Bowleg, Huang, Brooks, Black, & Burkholder, 2003; Greene, 2000). Frequent sexual objectification may contribute to low self-esteem and other indicators of distress (Moradi & Huang, 2008). Similar experi- ences have been noted among asexual men in the forms of social exclusion, isolation, invalidation of their asexual identity, and un- wanted sex (Decker, 2014; Przybylo, 2014). Regardless of perceived race or ethnicity, stereotypes of WOC were identified as a significant source of stress.

Attending to the nature of the source of distress for minority populations is paramount; here, distress may be induced by societal pressure to confirm to normative sexuality (Chasin, 2015). Disclosure as an anxiety-provoking task is also a recurring theme in asexuality research (Gazzola & Morrison, 2012; Foster & Scherrer, 2014; Jones, Hayter, & Jomeen, 2017; Scherrer, 2008). Participants reported that after disclosure, they have been objects of verbal harassment includ- ing suggestions that asexuality is illegitimate or a consequence of pathology. These stigmata contribute to macro level invisibility of asexuality. Stigma played a significant role in shaping comfort level, self-esteem, and community belongingness for participants. Explicit recognition of these stigma experiences may also promote healthy sense of self when the source of distress is externalized.“

“And Now I’m Just Different, but There’s Nothing Actually Wrong With Me”: Asexual Marginalization and Resistance (Study Published in the Journal of Homosexuality)

"A number of scholars studying asexuality have argued that although Western society is certainly “sex negative” in some ways, Western society also systematically privileges sexual identifications, desires, and activities while marginalizing different forms of non- sexuality, to the detriment of asexually identified individuals (for example, Chasin, 2013; Emens, 2014; Gupta, 2015a). According to some scholars, asexual commu- nity formation poses a challenge to this society-wide system of “compulsory sexuality” or “sex-normativity,” calling into question deeply held assumptions about sexuality and relationality (Chasin, 2013).A number of studies have explored one or more of the negative impacts of contemporary sexual norms on the lives of asexually identified individuals. According to this scholarship, asexually identified individuals can face pathologization (Foster & Scherrer, 2014; Robbins, Low, & Query, 2015), difficulties in relationships and social situations (Carrigan, 2011), and disbelief or denial of their asexual self-identification (MacNeela & Murphy, 2014).In response to a direct question about whether they had ever felt stigmatized or marginalized as a result of their asexual identity, more than one half of the interviewees answered “yes,” more than one quarter answered “maybe” or “in some ways yes, in some ways no,” and around 20% answered “no.” In addition, all the interviewees described at least one negative experience attributable to compulsory sexuality. Here I offer a typology of these negative impacts of compulsory sexuality: pathologization, isolation, unwanted sex and relationship conflict, and the denial of epistemic authority. It is important to emphasize that what follows should not be taken as direct evidence of marginalization, stigma, or discrimination but as the interviewees’ interpretations of and narratives about particular life experiences.Unwanted sex and relationship conflict

In response to a question about their relationship history, almost two thirds

of interviewees reported that social norms about sexuality and relationality

and the invisibility of asexuality had negatively affected their interpersonal

relationships. Ten interviewees (all female) described engaging in consensual but unwanted sex as a result of social pressure and pressure from a partner. Explaining why she had engaged in what she considered consensual but unwanted sex, Marcie, 19, said, “there’s not a lot of visibility for asexuality so when you’re young and you don’t really know that that’s a genuine orientation that you can embrace...you have all of society telling you, ‘You should want to be doing these things....’ So, it tended to get a little sexual but I was always trying to avoid that.” Christine, 21, described the following experience:

The guy I lost my virginity to, I had been in a relationship with him for about a year and I guess I just felt like, well, you know, I need to do this...And everybody was like, ‘Oh, you were raped and that’s awful.’ And like yeah, I guess. I should have said no. I could have said no, but I didn’t. I thought that this is what everybody did in their free time, and so I was trying to be like everybody else.

It is important to note that, according to a substantial body of research, a

significant percentage of both women and men report engaging in consensual but

unwanted sex for some of the same reasons as those given by the interviewees in

this study (e.g., Gavey, 2005; Impett & Peplau, 2002; Muehlenhard & Cook, 7

1988). Thus it is possible that the system of compulsory sexuality negatively affects asexually identified and non–asexually identified people in some of the same ways.

Overall, according to approximately two thirds of the interviewees, sexual norms and the invisibility of asexuality had made it difficult to maintain romantic relationships with sexual partners. For example, Clare, in her late 20s, talked about the fact that before she had found the word asexual, she did not know how to communicate her wants and needs, which made negotiation with a partner difficult. She said, “I’m not really like even opposed to [sex]—like I think I could do a long term relationship with someone if they understood that I was just not going to be into it as much, but like I didn’t know that at the time. So it was very hard to commu- nicate.” Kerry, a recent medical school graduate, talked about the fact that because potential partners maintain socially influenced expectations about sex and relationships, negotiating the sexual aspects of a relationship are more difficult. She said, “Even trying to like kind of negotiate that kind of thing, it’s like your partner knows that you’re not as into it as you should be or a sexual person would be...[your partner] can’t not be hurt by that because they don’t understand that it’s not that I’m [just] not attracted to [them]” (emphasis added). On the other hand, two interviewees reported that they had managed to successfully negotiate the sexual aspects of relationships with sexual partners in the past, and one interviewee was currently in a relationship with a sexual partner.

Finally, contemporary Western society’s privileging of sexual relationships over nonsexual relationships was perceived by some interviewees to have had negative effects on their ability to maintain long-term friendships. Two interviewees mentioned that it was hard for them to maintain friendships because their friends often wanted to turn friendships into sexual relation- ships. Three interviewees talked about their sense that their friends prior- itized sexual relationships with others over nonsexual friendships. Sarah described her sense of this as follows:

I feel like a lot of sexual people, they’re like, ‘Oh, you’re my friend,’ but then like maybe they start dating someone else and they lose contact with a lot of their friends. Like a lot of people become really invested in their sexual relationships. And then they’re like, ‘Oh,’ and your commitment with them sort of vanishes—this happened to me once. It was really hard because I had all this commitment toward the friendship and then the friendship just sort of evaporated on me.

Chris offered another example of this phenomenon: “I’ll be really good friends with someone, but I have to step aside whenever they get in a romantic relationship in a way that no one’s ever stepped aside because of a relationship I have with anyone.” Again, this kind of experience may not be unique to asexually identified individuals, as compulsory sexuality may effect sexual people in similar ways."

Asexual People’s Experience with Microaggressions (City University of New York)

(This study is a 45-page document detailing the types, sources, and effects of microaggressions. For space restrictions, I have only included the conclusion.To read the complete study, check out the library.)“This study was done to discover if asexual people experience microaggressions, and if so, how the microaggressions manifested, who they came from, and what mental health effects they may have. Information from this study was also collected to inform further research, as well as increase competency for mental health care providers that have asexual clients. This study supports the proposition that asexual people do experience subtle discrimination known as microaggressions. The themes found were similar to the themes found in other research on LGBTQ identities (Nadal, 2011). The microaggressions came from the expected sources similar to other microaggression studies, such as family, friends, and the media. They did report some more overt forms of discrimination in the form of attempted sexual assault and nonconsensual touching that appeared to intersect with their gender identity; the participants all identified as women and women report a 1 in 5 rate of rape in the United States (NSVRC, 2015).

Discrimination has long been associated with negative mental health outcomes and distress, and microaggressions are starting to be associated with negative mental health outcomes as well (Nadal, 2011). It is important to know that asexual people are facing this form of discrimination and how it affects them so it can be combated and access to support and needed mental health care can be provided. Microaggressions also can come from healthcare providers and even mental health providers, as indicated in this study and others (Shelton & Delgado-Romero, 2011). Providers should be able to recognize the common microaggressions against asexual people so that they can avoid perpetuating microaggressions in the future and they can provide more competent and compassionate care. Microaggressions and discrimination have been previously shown to have negative effects on the mental health of LGB individuals, and the asexual participants in this study reported that microaggressions caused them increased anxiety, relationship stress, discomfort, and depression. Considering LGB people also report higher levels of mood disorders and personality disorders compared to heterosexual people, it is important to know what may be contributing to this, as they may be a population at a greater risk of negative mental health outcomes and in need of greater care (Yule, Brotto, & Gorzalka, 2013). They also may be seeking therapy more frequently because of their mental health and it is important to be culturally competent and aware of what asexual people face as a population. If health providers become aware of the experiences of asexual people, these individuals would be spared the need to explain their sexual orientation and freed from experiencing microaggressions in a health care setting where they need treatment.”

Asexuality: A Minority in Need of Understanding (http://thewip.net/education/asexuality-a-minority-in-need-of-understanding/)

“Another all-too-common response is to suggest that people who are asexual simply have not had decent sex. This opens the door to rape culture, where sexual people believe it is okay to pressure asexual people to engage in unwanted sex because it might help “fix” the “problem.” CJ Chasin, a graduate student who researches sexuality at the University of Windsor, Canada cautions, “Of the two small groups of asexual and non-asexual women in my study (who had agreed to unwanted sex) with romantic partners who were men, participants in both groups generally had these experiences very frequently during the course of these relationships. And both groups actually experienced quite a bit of sexual coercion in those relationships overall. These asexual women as a group experienced particularly much [more] sexual coercion, including sexual coercion that was specifically related to their asexuality.” Clearly, for some asexuals, entering a romantic relationship with a sexual person can be riskier than for sexuals.”

When You’re An Asexual Assault Survivor, It’s Even Harder To Be Heard (Article on BuzzFeed)

This article only mentions one statistic but it is still quite relevant, so I went ahead and included it.

"Because public discourse often overlooks and even outright dismisses asexuality itself, it follows that ace stories of harassment and assault aren’t widely heard, let alone accepted or understood, among those who don’t identify as ace. But that doesn’t mean they don’t happen: In the 2015 asexual community census, a volunteer-run project, 43.5% of nearly 8,000 aces surveyed reported having experienced some form of sexual violence (including rape, assault, and coercion)."

"Conversely, ace women’s experiences can blend into those of other women’s generally. “Obviously, I can’t separate being a woman from being an asexual person, because I’ll always be both,” said Julie Sondra Decker, 40, the author of the 2014 seminal ace book The Invisible Orientation. “I do find that a lot of what has happened to me has happened because I’m asexual or partially because I’m asexual. ‘Oh, that just happened to you because you’re a woman,’ or ‘That just happened because of sexism.’ … I see a lot of downplay of how much being asexual factors into that.”"

"Aces often talk about the idea of the “unassailable asexual,” which is someone whose asexuality is begrudgingly accepted by the mainstream because there’s no other plausible reason for their disinterest in sex: someone who’s white, cis, neurotypical, not “too old” or “too young,” and with no disabilities and no history of sexual trauma. If someone who could seemingly have their pick of sexual partners abstains from sex, then they must not have “chosen” this identity after all. Aces from more marginalized backgrounds often have more difficulty finding acceptance, let alone becoming public faces for the community.Aces also fight the misconception that they can’t be assaulted because they’re never in sexual scenarios to begin with. “If you’re not sexually attracted to people, you’re not in those situations to be sexually assaulted. So you know, are there even asexual victims?” Devin said, parroting a generalization she’s heard. “Which, obviously there are, you don’t need to be in a sexual situation to be a victim or a survivor.” Plus, many aces do sometimes pursue romance and sex.“I feel that because asexuality is perceived as an entirely ‘nonsexual’ identity by many outside the ace community that it’s unfortunately easy for ace survivors of sexual harassment and assault to be left out or excluded from the conversation,” Paramo said."

Battling Asexual Discrimination, Sexual Violence And ‘Corrective’ Rape (Article in The Huffington Post)

This is another article that is more qualitative rather than quantitative that I decided to include.

"Sexual harassment and violence, including so-called “corrective” rape, is disturbingly common in the ace community, says Decker, who has received death threats and has been told by several online commenters that she just needs a “good raping.”“When people hear that you’re asexual, some take that as a challenge,” said Decker, who is currently working on a book about asexuality. “We are perceived as not being fully human because sexual attraction and sexual relationships are seen as something alive, healthy people do. They think that you really want sex but just don’t know it yet. For people who perform corrective rape, they believe that they’re just waking us up and that we’ll thank them for it later.”In April, a heated debate sparked online when an asexual Tumblr blogger wrote about corrective rape.“There is a real fear even among the asexual community that people who identify as anything other than heterosexual will be harassed and assaulted,” wrote “Angela,” a self-identified aromantic ace. “They have a reason to be upset and a reason to be afraid, it has happened to many people before.”"

"Asexuals and ace activists say the conversation about sexual assault in the asexual community is part of the wider societal discussion about rape culture generally and about corrective rape in the queer community specifically. They also say it speaks to a bias and an invisibility that asexuals face in everyday life.Indeed, aces have in the past been characterized by members of the mainstream and religious media as abnormal, unhappy and repressed.In a 2012 Fox News segment about sexologist Anthony Bogaert‘s book Understanding Asexuality, host Greg Gutfeld and a panel of guests mocked the asexual identity, treating it as something invalid or exaggerated.“[T]hey have a lack of ... sexuality, so they’ll be kind of treated as lepers — asexual lepers, if you will,” Gutfeld said in the segment.Yet few outsiders appear to know much, if anything, about the community.In the beginning of filmmaker Angela Tucker’s 2011 documentary “(A)sexual,” members of the general public try — and fail — to grasp or explain asexuality. While many quickly connect asexuals with organisms like mosses and amoebas, one man asserts with conviction that there’s “no such thing” as asexual human beings.Last year, the apparent bias against aces was corroborated by a landmark study conducted by Brock University researchers Gordon Hodson and Cara McInnis. The study found that people of all sexual stripes are more likely to discriminate against asexuals, compared to other sexual minorities.“Most disturbingly, asexuals are viewed as less human, especially lacking in terms of human nature,” the study authors wrote. “This confirms that sexual desire is considered a key component of human nature and those lacking it are viewed as relatively deficient, less human and disliked.”"

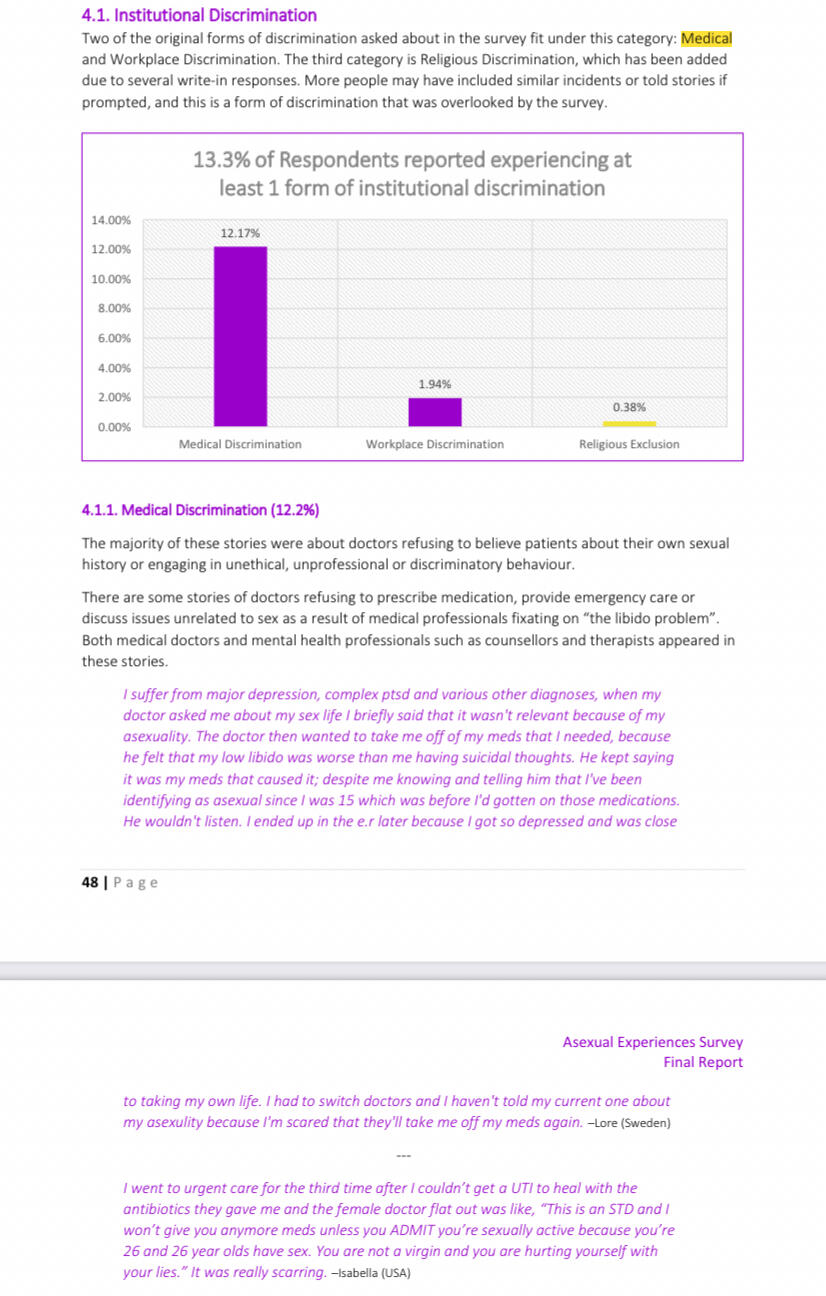

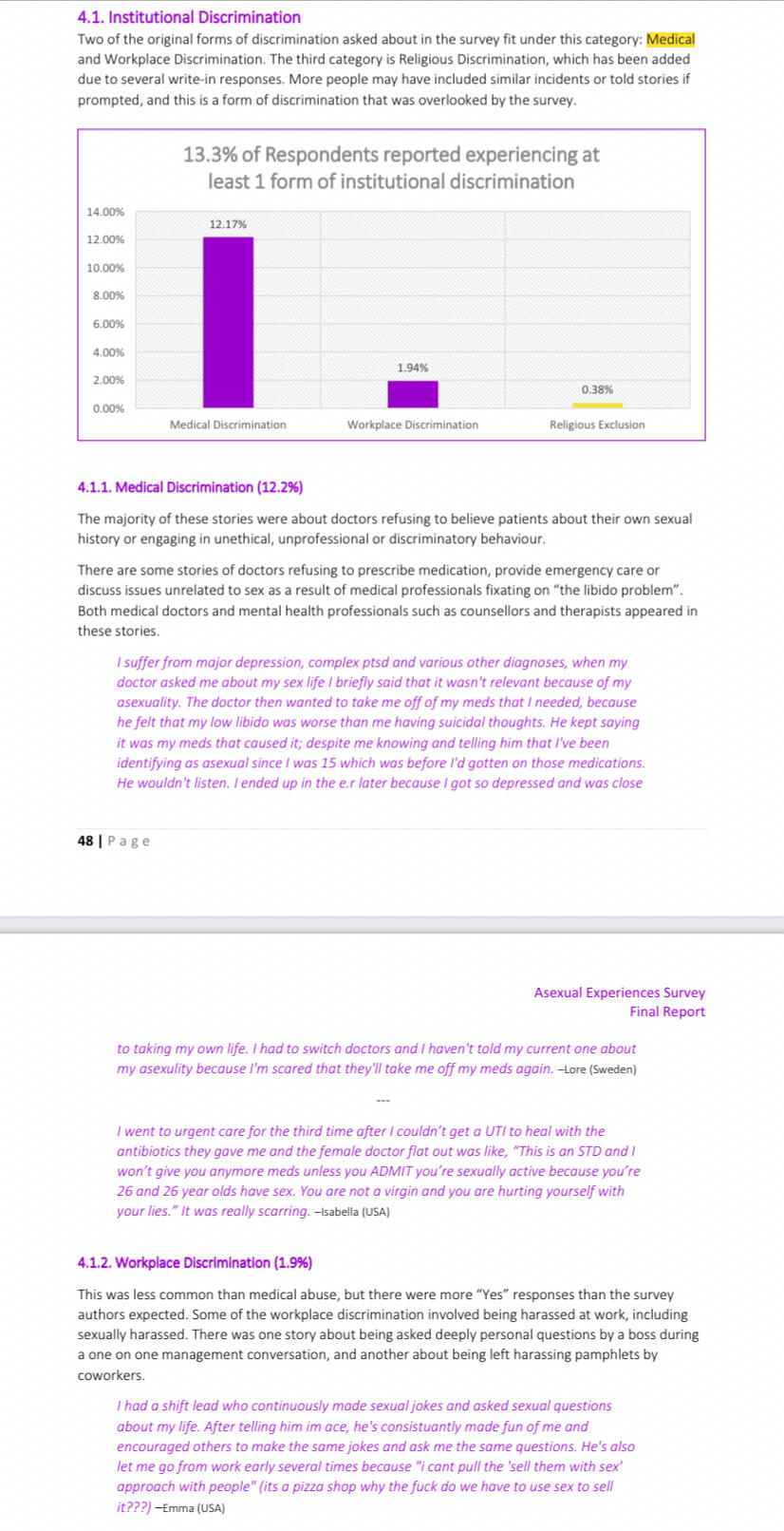

Medicalization and Discrimination in The Health Industry

A Lack Of Sexual Attraction Is Still Widely Seen As A Medical Problem

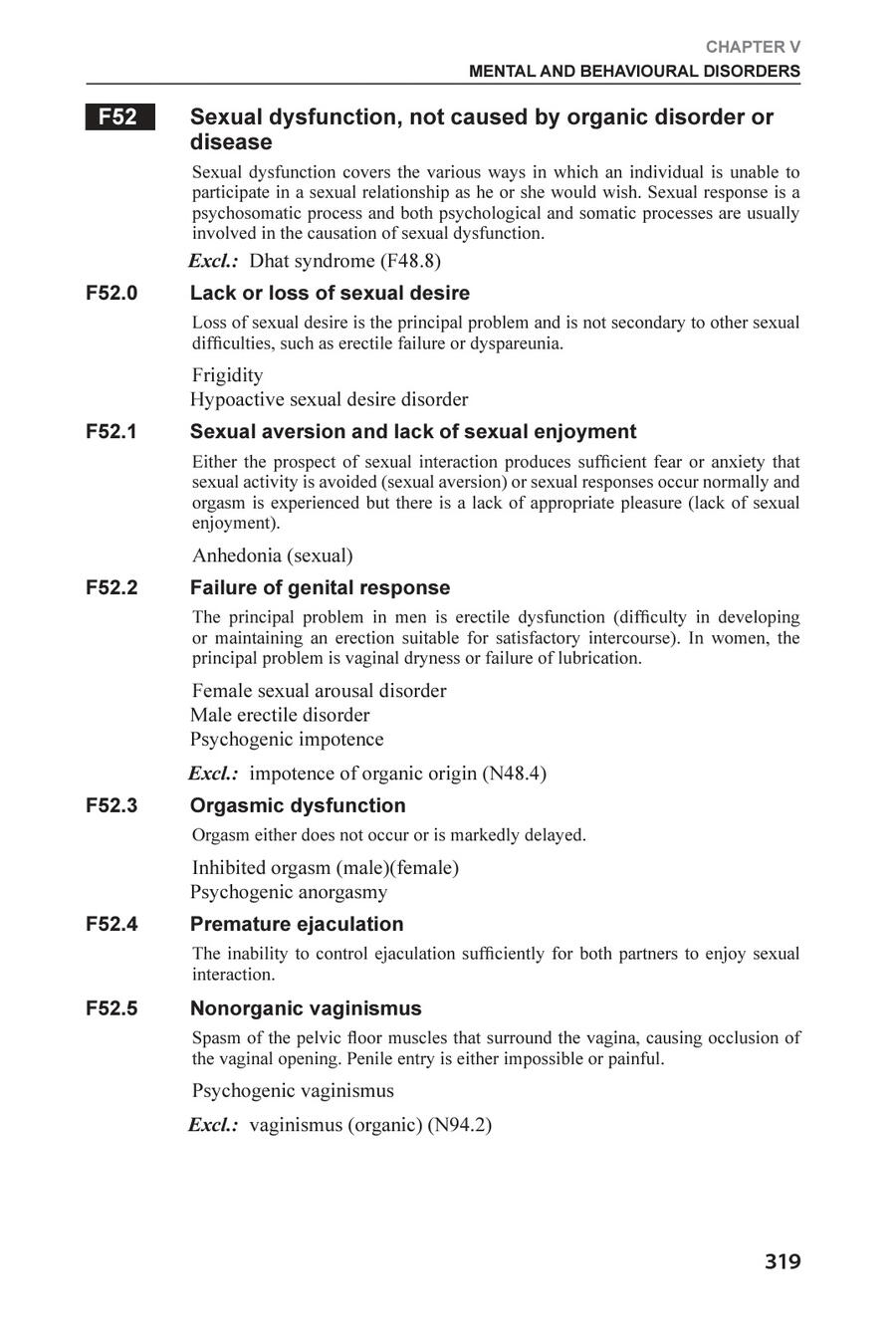

Perhaps the most common area of marginalization of asexuality is in the medical field. Until recently, asexuality was considered a mental disorder by the DSM 5, and even now most doctors have trouble understanding a lack of sexual attraction. Hormone therapy and psychological referrals are still common, which makes asexuals afraid to come out to their providers or, in worst cases, afraid to seek healthcare altogether.Contact @asexualresearch on Twitter or [email protected] for articles that should be added, questions, or concerns!

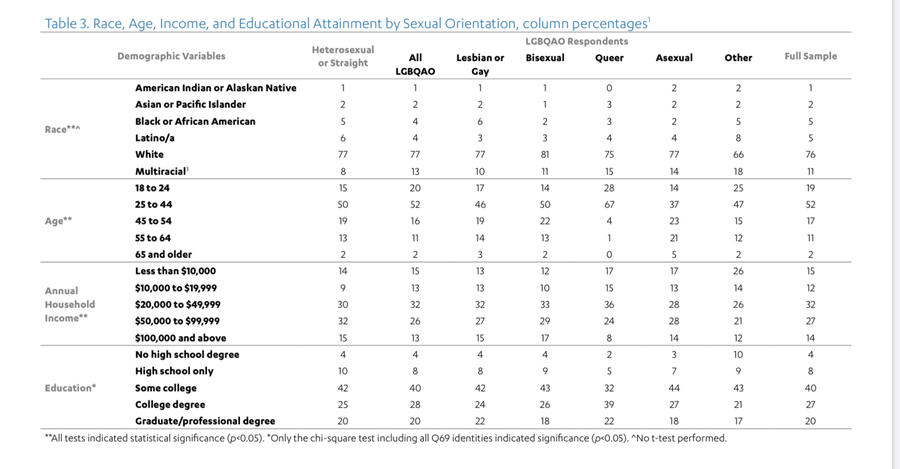

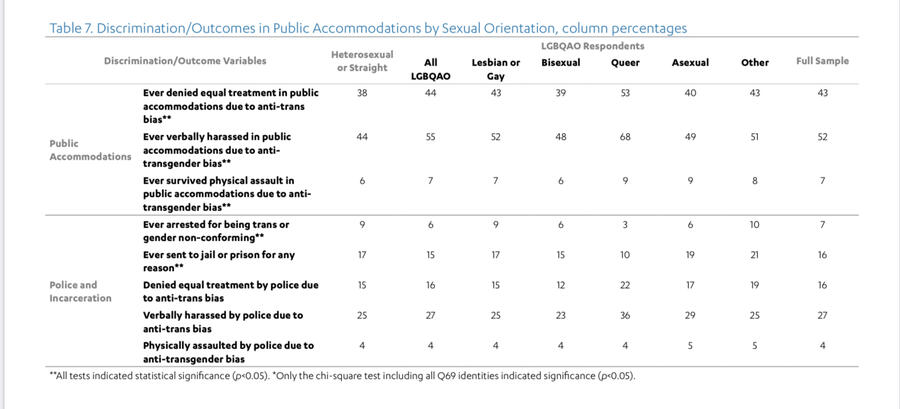

LGB within the T:

Sexual Orientation in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey and Implications for Public Policy

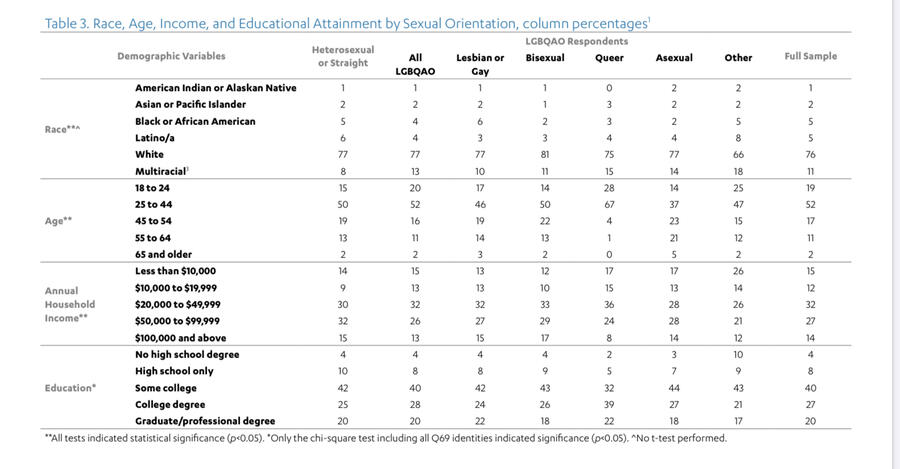

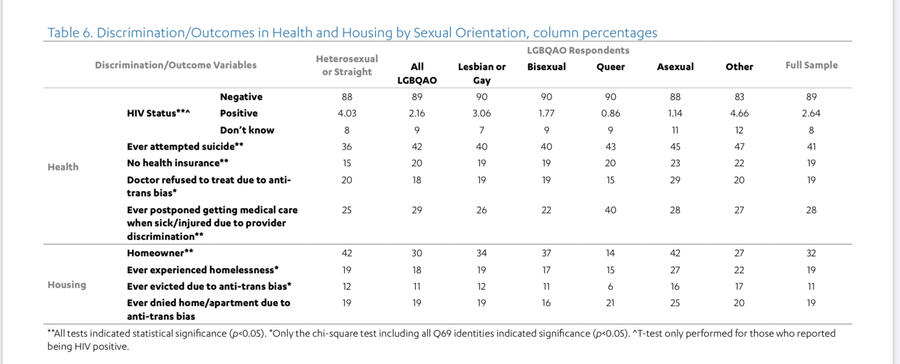

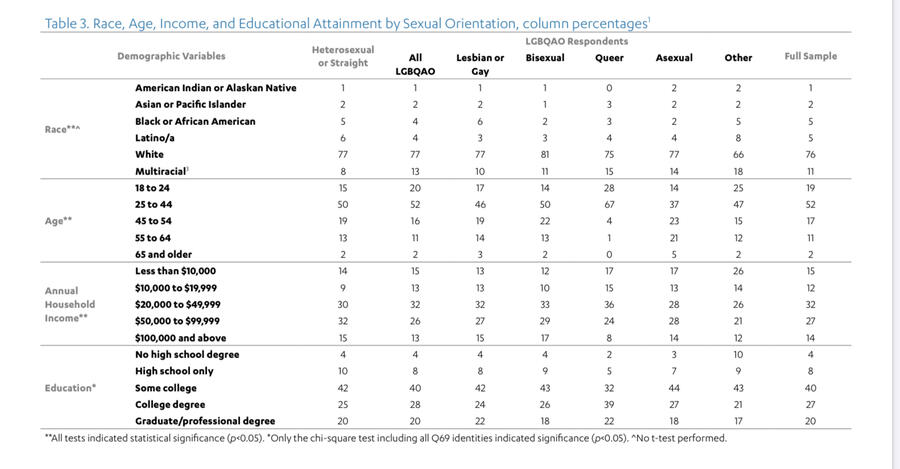

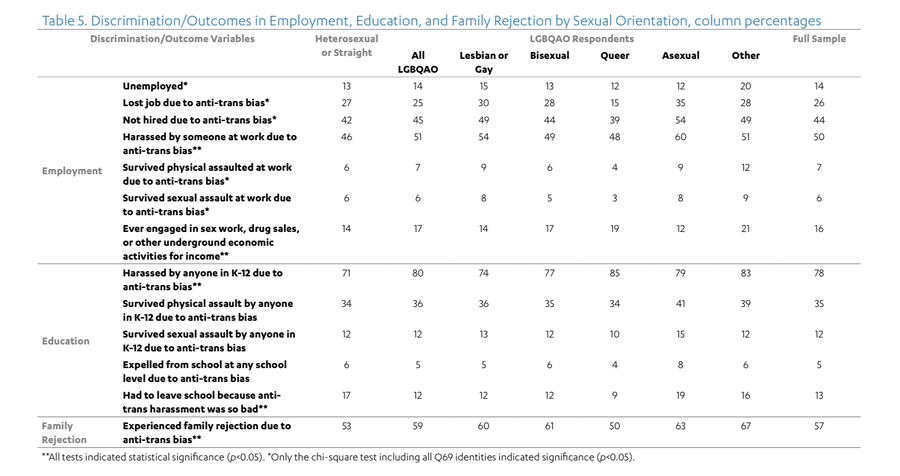

This study examines sexual orientation and discrimination experienced by transgender people, an important step in analyzing the intersectionality of gender identity and sexual orientation.An important note about the data: Although only 264 asexual people responded, the researchers analyzed the data to make sure it was significant. The data with two asterisks are statistically significant, and those with one are statistically significant in the context of the complete study.

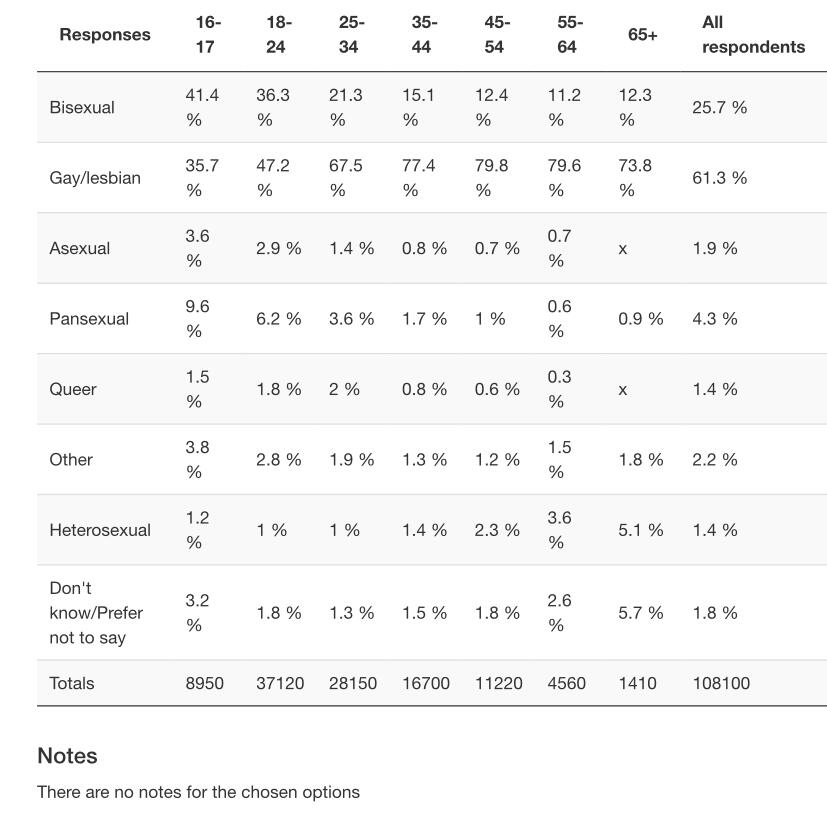

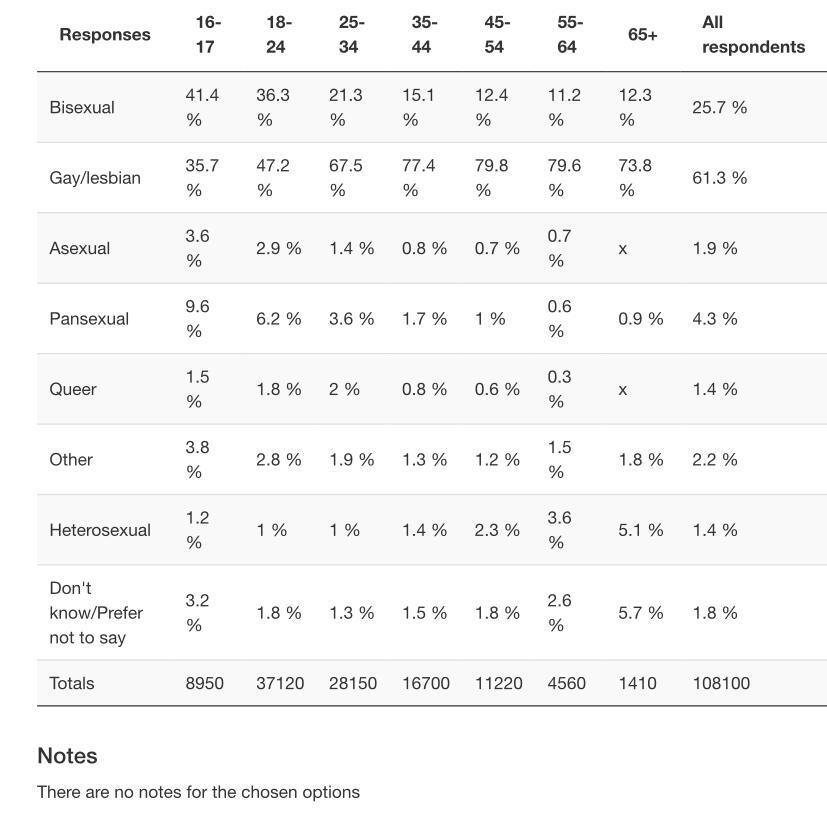

Age of Participants (Interestingly, asexual respondents skewed older)

Health

National LGBT Survey 2017 UK

The link above leads to the interactive data set. In the PDF library I have also included the analysis provided by researchers that the quotes arise from.

A Note On The Sample Size: “Due to the lack of data on the LGBT population, it was not possible to gross the survey findings to be representative of all LGBT people, nor was it possible to weight the data, for example for non-response, as it was not based on a sample. Similarly, confidence intervals and statistical testing were not appropriate because the data was not based on a representative sample.

The results presented in this survey nonetheless constitute the findings on the experiences and views of over 100,000 LGBT people, making it one of the largest collections of empirical evidence from this group to date.“

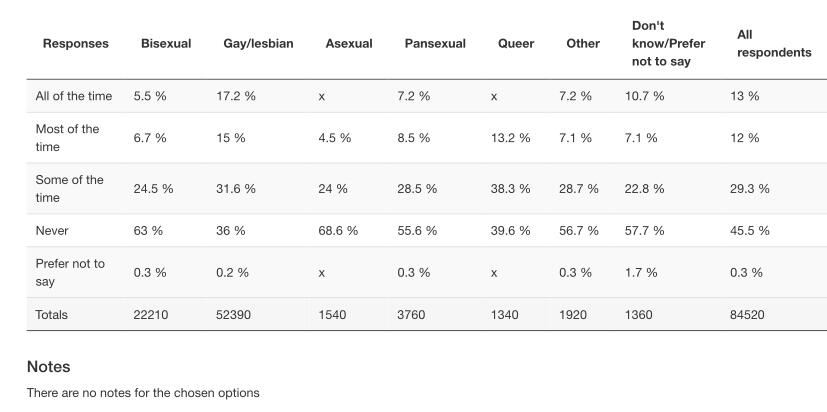

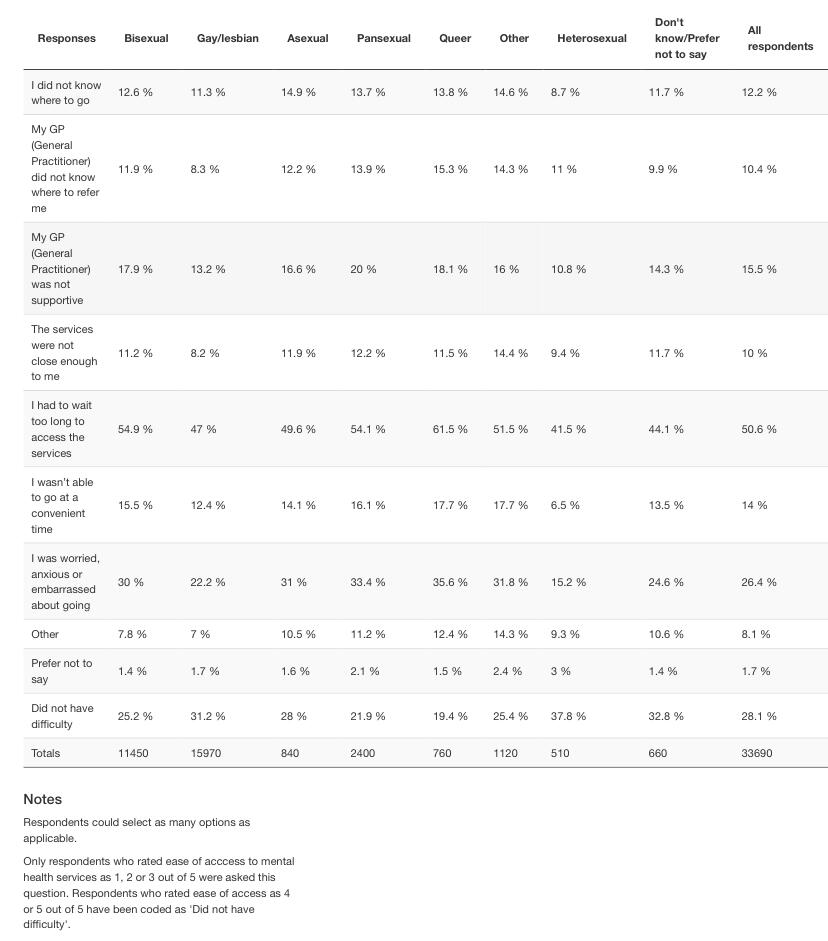

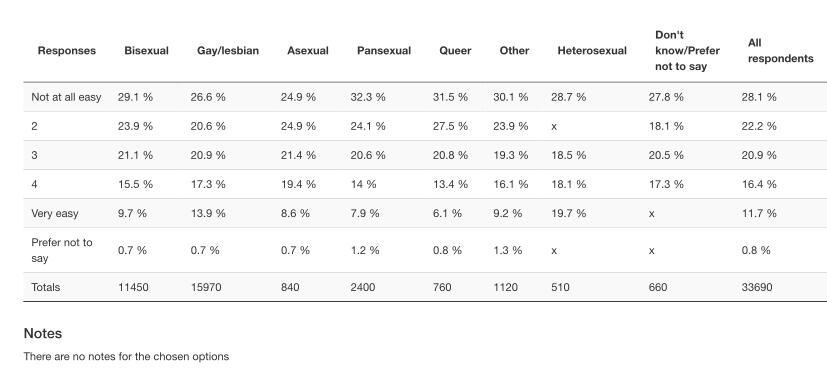

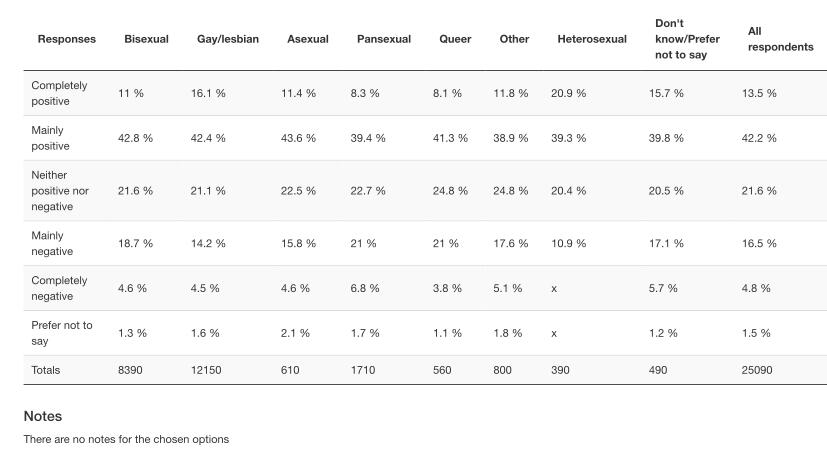

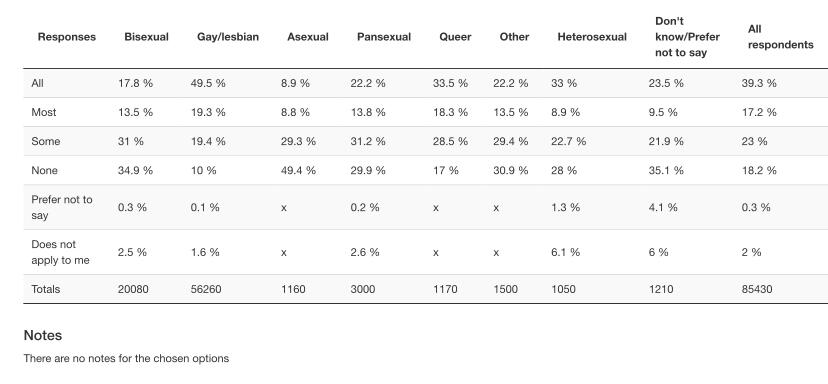

“Bisexual respondents were the least likely to have undergone or been offered conversion therapy (5%), and asexual respondents the most likely (10%) .”“ Amongst cisgender respondents, queer respondents (86%) were particularly likely to have accessed or tried to access healthcare services, whilst asexual respondents were the least likely to have done so (73%) (Annex 8, Q68).”“ Queer (23%) and asexual (21%) respondents were more likely to have experienced at least one of the listed negative experiences [with a medical professional] than gay and lesbian (14%), pansexual (14%) and bisexual respondents (11%) (Annex 8, Q72).”“ The most frequently stated reason for not having disclosed or discussed sexual orientation with healthcare staff was that respondents had not thought it was relevant (84%) (Annex 8, Q71). Amongst cisgender respondents, asexual (22%), queer (18%) and those identifying as having an ‘other’ sexual orientation (17%) were particularly likely to say that they had feared a negative reaction (Figure 8.7).““ Amongst cisgender respondents, those with less common sexual orientations were particularly likely to say that disclosing their sexual orientation had a negative effect on their treatment, with 26% of asexual, 13% of queer and 10% of pansexual respondents reporting this, compared to 7% of gay and lesbian respondents (Figure 8.10).”“Intersectionality is worthy of note in respondents’ perception of access, as trans respondents who identified as heterosexual were more likely to rate access to mental health services ‘very easy’ (18%) than trans respondents with a minority sexual orientation, such as trans respondents who identified as queer (6%), pansexual (7%) and asexual (7%) (Annex 8, Q76).”“ Amongst cisgender people, those with less common sexual orientations were particularly likely to say that they had been ‘worried, anxious or embarrassed about going’ to sexual health services ranging from 8% of bisexual respondents to 12% of asexual respondents, compared to 6% of gay and lesbian respondents. They were also notably more likely to say that their GP had not been supportive, ranging from 3% of bisexual respondents to 8% of asexual respondents, compared to 2% of gay and lesbian respondents (Table 8.2).“

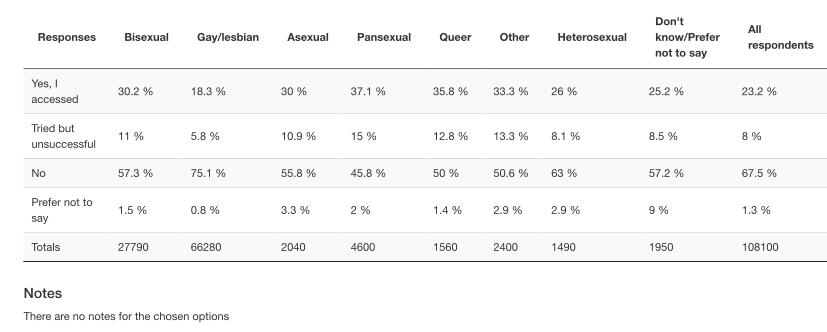

Have you ever had so-called "conversion" or "reparative" therapy in an attempt to "cure" you of being LGBT? Have you ever been offered this so-called "conversion" or "reparative" therapy?

Who conducted this so-called "conversion" or "reparative" therapy?

Who offered this so-called "conversion" or "reparative" therapy?

In the past 12 months, how often did you discuss or disclose your sexual orientation with healthcare staff?

In the past 12 months, why did you not discuss your sexual orientation with all healthcare staff?

In the past 12 months, did being open about your sexual orientation with healthcare staff have an effect on your care?

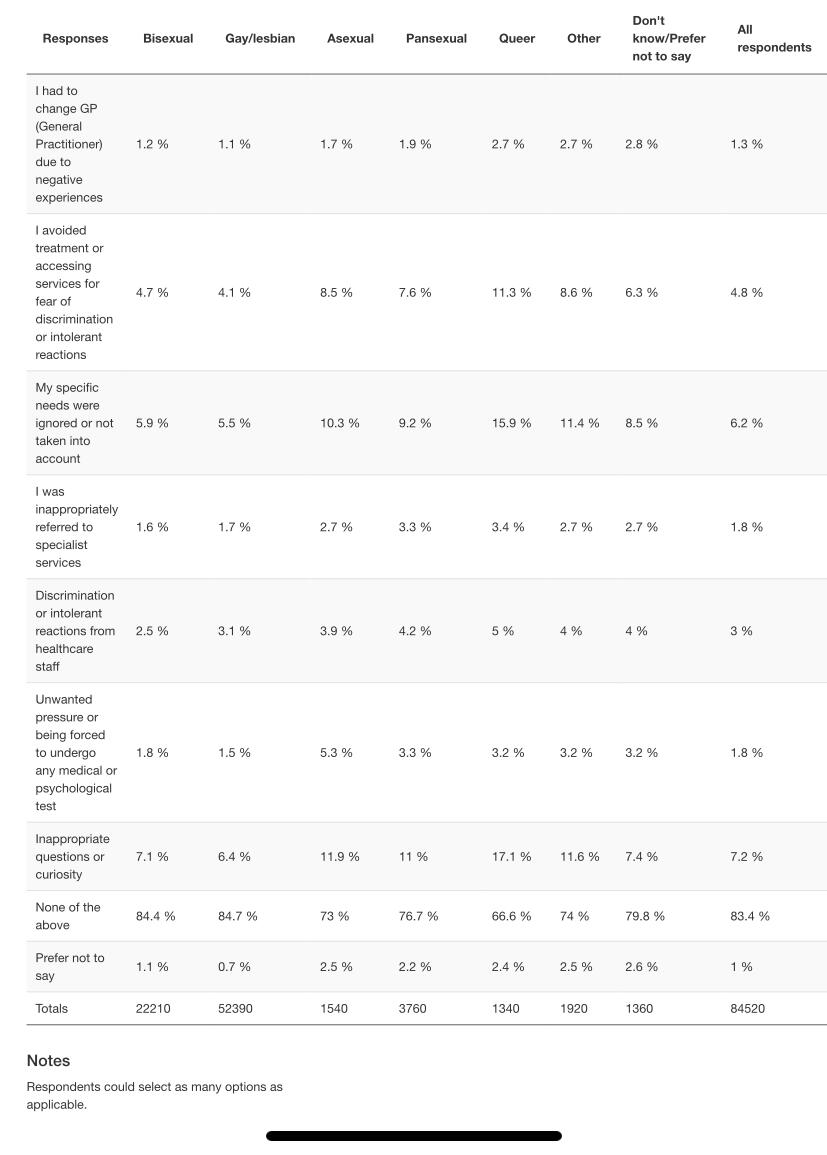

In the past 12 months, did you experience any of the following when using or trying to access healthcare services because of your sexual orientation?

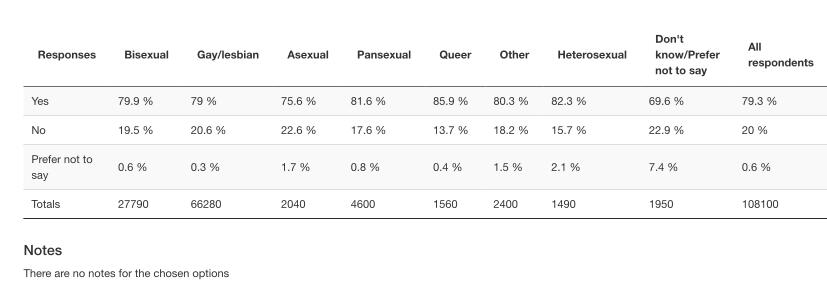

In the past 12 months, did you access, or try to access, any public healthcare services? For example, any services provided by the National Health Service (NHS) in England, Scotland and Wales, or Health and Social Care (HSC) in Northern Ireland. This includes in relation to your physical, mental or sexual health, or your gender identity, and includes routine appointments with your GP (General Practitioner).

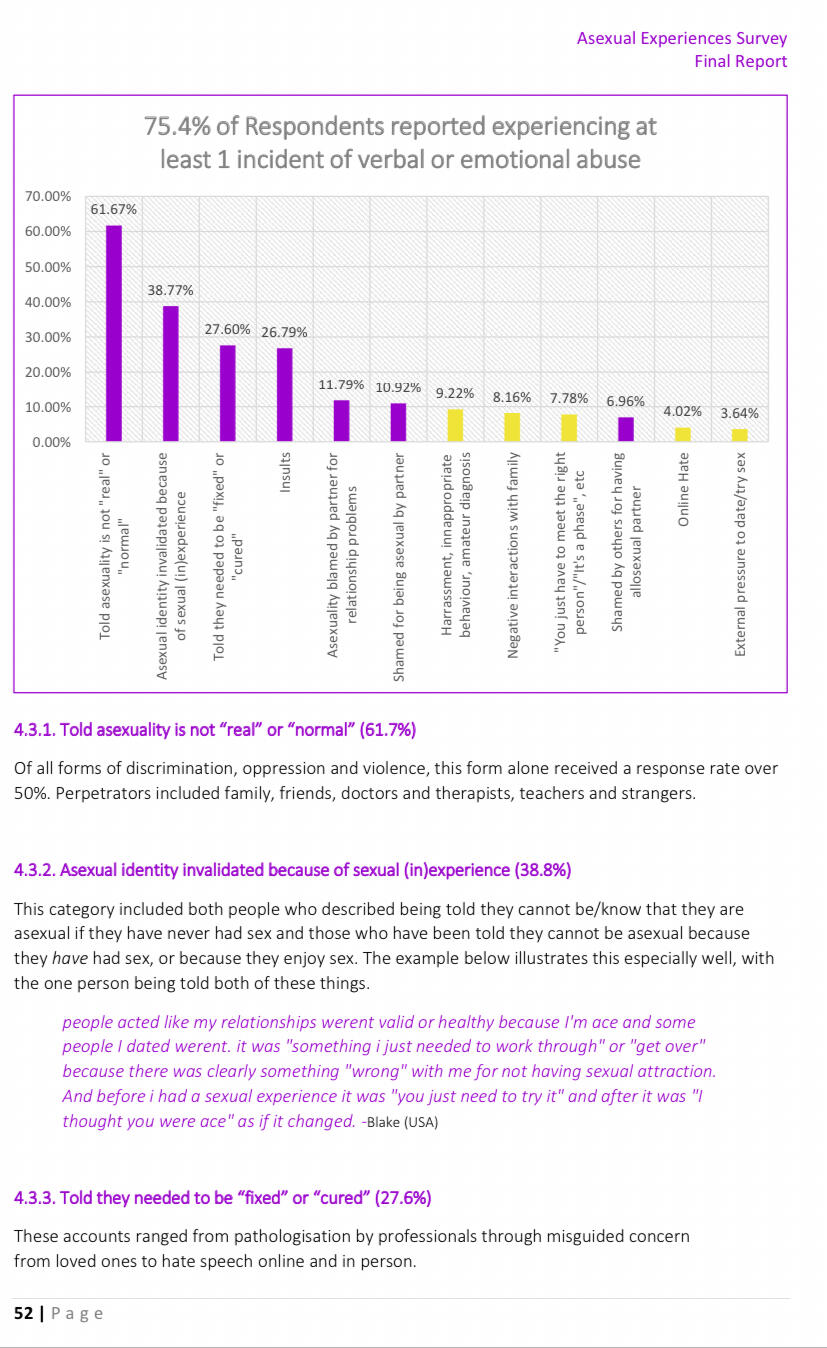

Age of Respondents (relevant in analyzing access to healthcare)